After the clear failure of socialism in the 20th century and the various problems created by capitalism, many in the last 120 years have sought a “third way” economic system—an alternative to capitalism and socialism.

Catholics from Hilaire Belloc and GK Chesterton to our own John Kleve have promoted distributism as that third way, as Kleve writes in A Libertarian Defense of Distributism, “Perhaps it is best, however, to describe Distributism in terms of two things it is most definitely not: Socialism and Capitalism.”

Unfortunately for these well-intentioned Catholics, there is no alternative to capitalism and socialism and distributism is just a nicer form of socialism.

The Socialism-Capitalism Spectrum

As with everything, definitions are crucial to a productive conversation. We will use the modern dictionary definitions of socialism and capitalism to reduce confusion. Socialism is the economic system “in which the ownership and control of the means of production and distribution, capital, land, etc., by the community as a whole, usually through a centralized government” and capitalism is the economic system “in which investment in and ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange of wealth is made and maintained chiefly by private individuals or corporations, especially as contrasted to cooperatively or state-owned means of wealth” (Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s economic liberalism).

This is a clear distinction and it’s also a dichotomy. Either some property is owned by an individual or the state. There really is no Schrödinger’s cat situation in which some property is owned both by the individual and by the state.

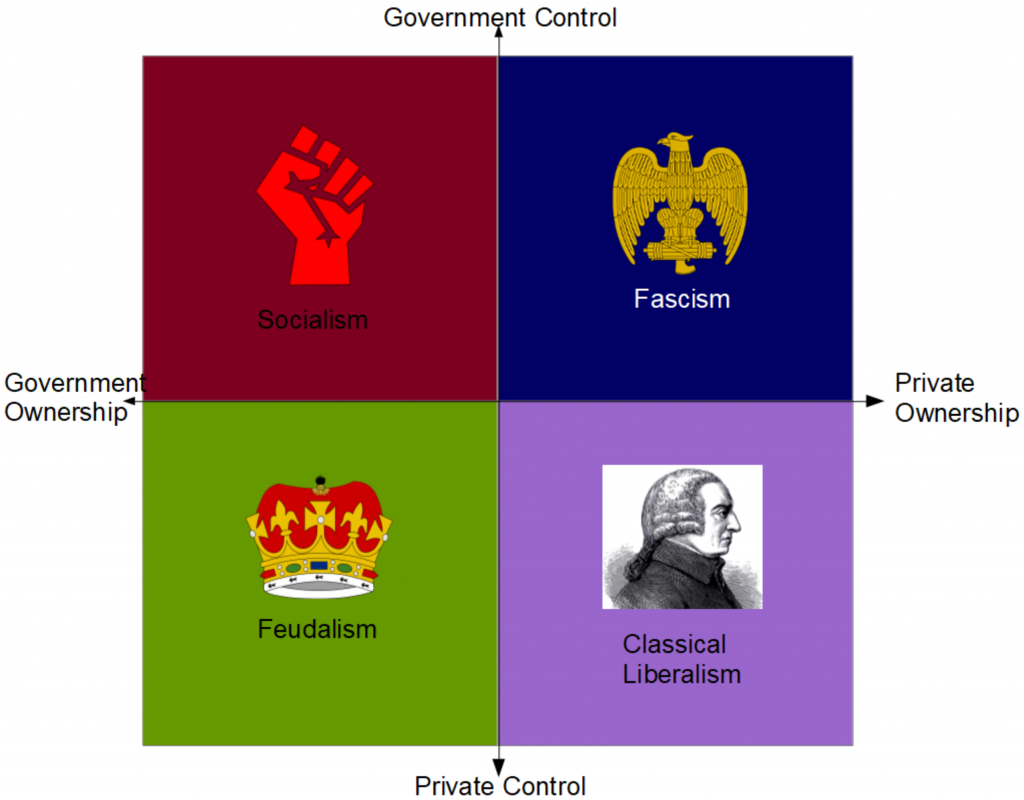

Kleve argues, however, that there are hybrid systems, which separate the ownership and control components of the means of production. He says that there is a system in which the individual is the owner but the state has control of any given means of production: fascism. Yet another system is that in which the state is the owner and the individual controls the means of production: feudalism.

This is certainly a compelling take but can you really own something without controlling it? Venerable Archbishop Fulton Sheen would appear to agree with Kleve. In Freedom Under God, Sheen makes the argument that ownership and control are distinct and that ownership of property is personal while the use of property is social. He argues one may legitimately own something but there are always restrictions on what you can do with it. For instance, you may rightfully own a gun, but you may not use it to kill your mother-in-law.

You may not rightfully do whatever you want with your rightful property. You may legitimately own a wooden club, but you may not rightfully use it to bash me over my head and steal my stuff.

However, that restriction is a natural result of the right to private property itself. In order to maximize individual ownership to private property (the definition of capitalism), a system must prohibit the violation of one’s negative rights to life, liberty, and property. A system that allows someone to violate another’s negative right to property through theft like the example above is not capitalism. It’s much more akin to socialism as St. Augustine noted in City of God, “Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms?”

Any control imposed on an individual’s property beyond the natural restriction of the non-aggression principle, whether illegal or otherwise constitutes a violation of negative rights and a departure from capitalism. Seen in this light, ownership and control of property are tightly bound. One only owns his property to the extent that he is able to control it and the maximum ownership/control one has is in a free market that adheres to the non-aggression principle.

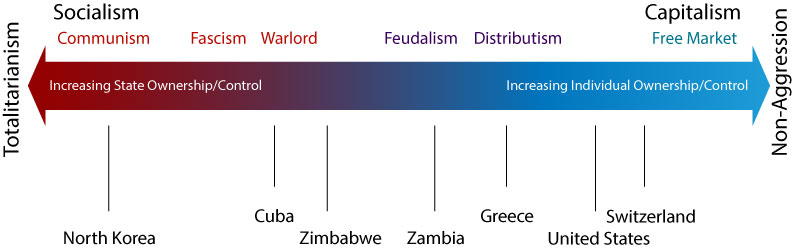

Using this frame, we can apply economic systems to a single axis.

Granted, there is no pure capitalism or pure socialism in practice right now (the closest we have to totalitarianism is North Korea with a Freedom Index of 5.2 and the closest we have to non-aggression is Singapore with a Freedom Index of 89.7 out of 100). But there also isn’t a “third way”. We’re stuck on a socialist-capitalist spectrum and any limits on the ownership/control of individuals that distributists want to impose, the more socialism they are promoting.

Problems with Capitalism

While distributists clearly reject the evils of socialism, they also take issue with the capitalist end of the spectrum and are right to point them out.

Belloc was highly critical when he wrote: “Industrial Capitalism is the ‘robust child’ of the Reformation…. Everything about Industrial Capitalism—its ineptitude, its vulgarity, its crying injustice, its dirt, its proclaimed indifference to morals [making the end of man an accumulation of wealth, and of labor itself an inhuman repetition without interest and without savor] is at war with the Catholic spirit.”

Of course, I don’t think Belloc means to infer that there is no dirt involved in an agrarian distributist society, but his other criticisms are valid. But which of those criticism can rightly be blamed on capitalism and which should more correctly be blamed on the human condition itself? Let’s explore.

Inequality

GK Chesterton saw the inequality that resulted from capitalism, defining the system as, “That economic condition in which there is a class of capitalists roughly recognizable and relatively small, in whose possession so much of the capital is concentrated as to necessitate a very large majority of the citizens serving those capitalists for a wage.”

And while the specialization of business owners and workers is not necessary in a pure capitalist system, history shows that it does tend to happen and inequality inevitably results.

Inequality is a notable boogieman of the modern democratic socialists like the ironically wealthy Bernie Sanders, but regulation has never seemed to get rid of inequality and while the inequality is no doubt larger in more capitalist systems, everyone is better off than they would be under a more socialist system. Margaret Thatcher made this point while defending her move toward free markets in the 1980s: “All income levels are better off than they were in 1979. What the right honorable gentlemen is saying is that he would rather the poor were poorer provided the rich were less rich.”

Conversely, an economy that is restricted from producing inequality is one that is stifled and fails to produce enough for all the people and everyone suffers but most notably the less wealthy. It’s true that immigrants to the United States in the 1800s met with difficult circumstances and had to work hard to earn much money, but they did it voluntarily because they were starving to death in their “more equal” native lands.

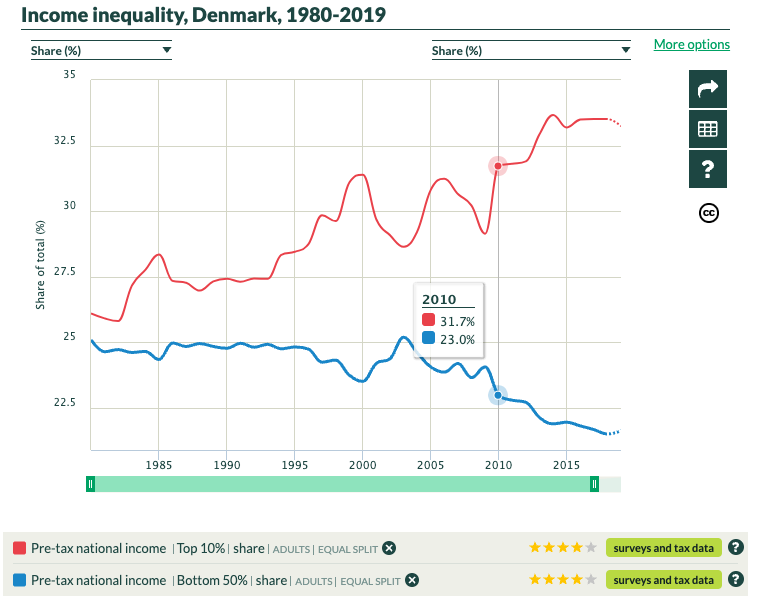

It’s ironic also that countries who people think have done a “good job on equality” in the last few decades have seen near exponential increase in that metric during that time, Denmark being an example:

It seems that top-down solutions to inequality are destined to fail and that inequality is inevitable.

Let’s also remember that forcing equality among unequals is inequality. If the wealthy gained their wealth through just means, it would necessarily be unjust to redistribute (or distribute) that wealth to those less well off. But, to avoid begging the question, let’s address whether those means by which capitalists gained their wealth were, in fact, just.

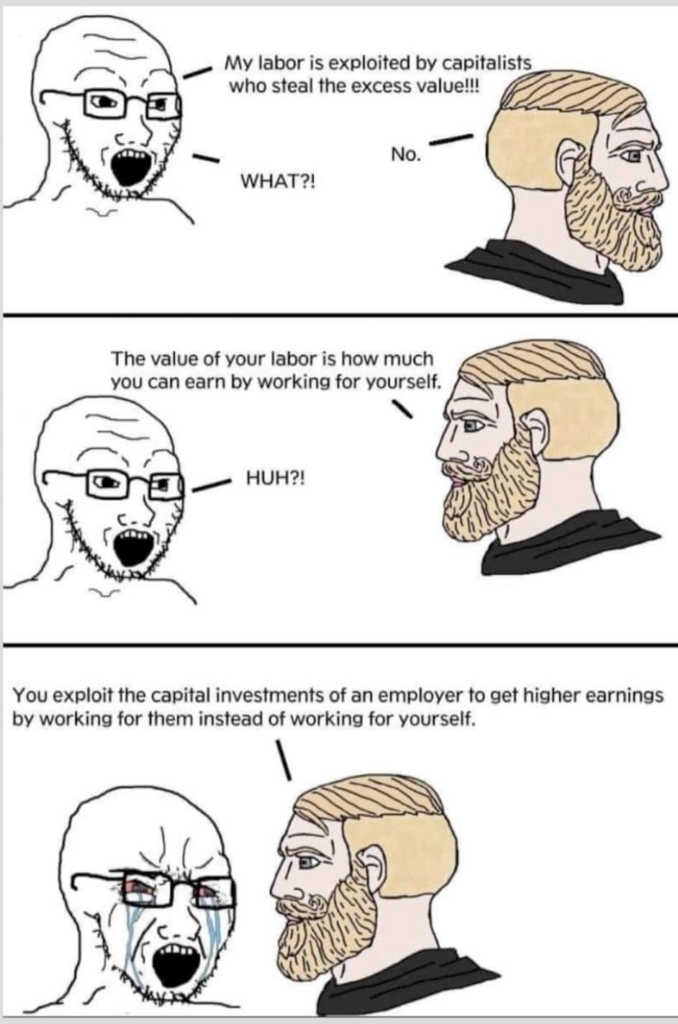

Exploitation

One of the main criticisms of capitalism I’ve heard from distributists is that it allows for people to make money “on the backs of others.” Fulton Sheen said that since the advent of finance, capitalism allows for the separation of responsibility from ownership of the means of production; capitalists sit back and own without having to work to produce additional wealth. They claim that the capitalist employer is exploiting the employee/worker as if only one of the parties in the economic exchange brings anything of value to the table.

But business owners do in fact bring something to the table—namely the capital—and the workers certainly benefit from that. The business owner or capitalist brings to the table the money to pay the employees. After all, labor without capital is just slavery.

He also assumes all the risk. If the business fails, the employees aren’t on the hook for that loss. They take their wage and look for another job.

For sure, it’s probably a better situation for the workers to own part of the company for which they work and this is certainly an acceptable arrangement in a capitalist system (e.g. with employee stock ownership plans), but most often than not, it’s not feasible. Creating a company is difficult and creating a company by committee is nearly impossible. That’s why it doesn’t happen that often. It’s not some conspiracy against cooperatives, it’s just that hierarchies tend to work better.

It’s not even like business owners sit back and eat bon bons all day. Most are active in management and labor for their company, not just investors.

And workers take advantage of the employer just as much the employer takes advantage of the employee because an employee often cannot make as much money doing his labor outside of the framework of that company. If he could, then he would. A voluntarily-agreed-upon employment contract is a mutually-beneficial situation.

We are seeing an increase in the owner/worker situation in which independent contractors sell their skills or rent their property through services like Uber, TaskRabbit, or AirBnb. These services empower much more dispersed ownership than the typical capitalist model and dismantles the Marxist and distributist dichotomy of oppressive owner versus oppressed worker. They are increasingly the same person thanks to technology.

Certainly, employees deserve a just wage, but that can only be what the market will provide. An employer deserves to make a profit on his employees based on his effort and risk and if he doesn’t, then he will shut down the enterprise altogether. An employee is worth only the value that he adds to the company, not what he thinks he deserves or what he needs to live a happy life (by whatever arbitrary standard he has for that).

And the beauty of a capitalist economy, though is that if you don’t like the employer-employee relationship, you can create a new one that is better suited to your purposes. You can be a socialist in a capitalist economy but you can’t be a capitalist in a socialist economy.

Stored Wealth

The ultimate question, however, is whether capital—or stored wealth—has any just value at all. Some claim that money itself, which allows for so much inequality and exploitation, is unjust. As some ’60s psychedelic rock bands would argue, “Money is the root of all evil today.”

But that’s a mis quote from the Bible. Timothy didn’t write that money was the root of all evil. He wrote that, “the love of money is a root of all sorts of evil, and some by longing for it have wandered away from the faith and pierced themselves with many griefs.” (1 Tim 6:10)

Money is simply a morally-neutral means of exchange and the storing of it is not evil in and of itself. In fact, it is the root of much good in the world.

Imagine Fred and John earn $50,000 a year working for the same boutique widget maker. John spends extravagantly and has nothing to show for it at the end of each year. Fred, on the other hand, spends frugally and saves $20,000 annually. By the end of five years, John has a lot of experience but is broke. Fred has sacrificed much but has stored $100,000 to buy the company. At that point, John would usually complain that it wasn’t fair that Fred had so much money. He didn’t complain that Fred had more money when he was spending extravagantly but only when Fred’s frugality paid off. Far from being immoral, this storing wealth is the explicitly moral thing to do because the wealth is not wasted in overconsumption.

As Our Lord teaches in the Parable of the Talents, it is okay and in fact the right thing to do to make the most of the wealth you are given—to make money on it and not squander it. He even justifies earning money on stored wealth through interest saying, “thou knewest that I reap where I sowed not, and gather where I did not scatter; thou oughtest therefore to have put my money to the bankers, and at my coming I should have received back mine own with interest.” (Mt 25:26)

Stored wealth has value and it is just to make money on that stored wealth. Any economic system that rejects this leads to wasteful spending and consumerism where “there shall be the weeping and the gnashing of teeth.” Many criticize capitalism for leading to consumerism, but it is the socialist system that limits investment and the Keynesian system that discourages saving through inflation that actually promotes consumerism.

The Best Socio-Economic System

It occurs to me that Belloc and perhaps all the distributists agree that capitalism represents the freest economy and that they do not oppose freedom but rather what men choose do with that freedom. Therefore, the distributist argues, we must limit freedom in order to produce the ideal socio-ecconomic system. But God gave us free will and He intended us to use it. He did so because without freedom to sin, we have no freedom to love. Similarly without the freedom to make inequality or specialized work, there is no freedom for all people to truly flourish.

With all the issues that people associate with free market capitalism, history has shown that it is the best socio-economic system thought up by man.

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic