Corporations have long been a boogieman of socialists and communists because, according to them, everything that is not owned by the collective is capitalist.

As Politstrum International states: “Modern corporations are large capitalist enterprises created specifically by the development of world capitalism.”

But they base this connection simply on the fact that corporations use capital to gain profits. As Politstrum continues: “[Corporations] have control over industries, markets, and the national economy based on a great concentration of production and capital in order to establish monopolistic prices and extract monopolistic profits.”

So-called “third-way” distributists like Venerable Archbishop Fulton Sheen agree that corporations are capitalists and use the critique of corporations as a reason to discount capitalism as a legitimate economic system.

But are corporations really components of capitalism?

If we can agree on the definition of capitalism as, “an economic system in which ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange of wealth is held chiefly by individuals as opposed to common ownership through the state,” it is clear that in several ways, the corporate system is more socialist than capitalist.

1. Corporations are communal

Despite governments designating corporations as legal “persons”, they are not real individual persons. They are, for the most part, groups of people with communal ownership of the means of production they control, albeit with different levels of ownership. In this way, corporations are much more like the communist state (which assumes ownership in common for all the citizens of the nation or country). Corporations are a sort of collectivist entity that emphasizes the group over the individual.

Corporations hold elections, have legislatures and presidents, and some even have their own currencies. They are basically non-geographical private states.

The socialist may rightly point out that everyone in a state has ownership but only people who buy into a corporation has ownership. But states have their buy-ins too in the form of taxes and they certainly are able to exclude people from ownership through imprisonment.

Without the monopoly of force, corporations’ collectivism is much less destructive than governments’, but it is still present and it’s still problematic.

The tragedy of the commons is a dilemma arising from the situation in which multiple individuals, acting independently, and solely and rationally consulting their own self-interest, will lower the yield of a shared limited resource, even to the point of ultimately depleting it, even when it is clear that it is not in everyone’s short or long term interest for this to happen. This happens with all communally-owned property such as corporate wealth, not just public lands.

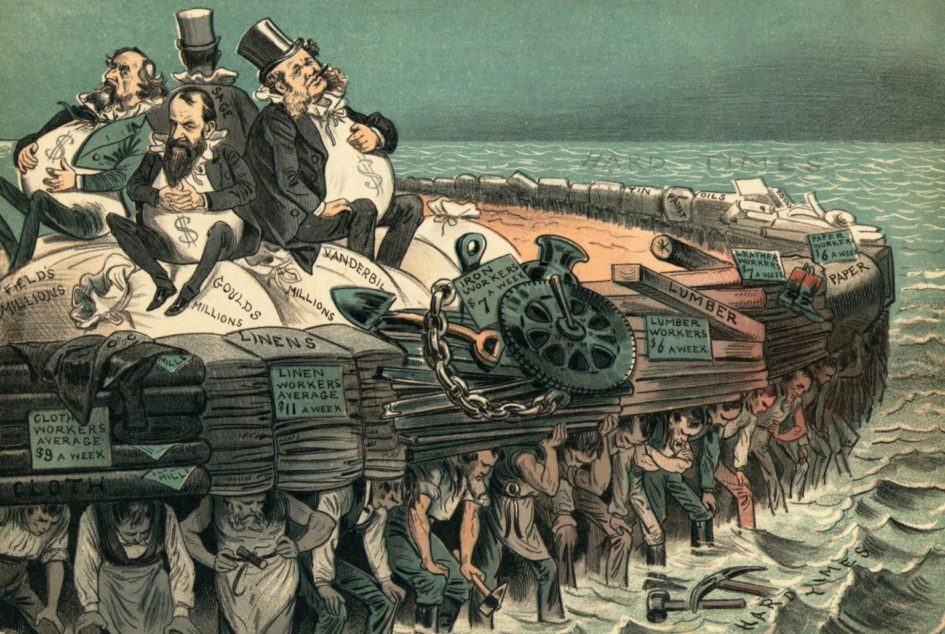

The shared property in corporations are exploited and depleted in many corporations just as they are in public lands. Specifically, corporations burn through “human capital” and resources with no concern for the people affected or the future of the company even. As Fulton Sheen wrote in Freedom Under God: “How many who own shares in corporations ever become concerned about the living wage of the employees? How many ever thought of any responsibility except their returns?”

2. Corporations separate ownership and management

One of the most common critiques of communism is that it creates a bureaucratic class that manages the ownership of the means of production. Sure, a lowly farmer may have a part in owning the common property, but what good is that when someone else completely controls it? Sure, in democratic socialist systems, the non-bureaucrats ostensibly have a say in who the bureaucrats are, but it’s such a small and insignificant say that it may as well not exist.

This is similarly problematic in corporations with stockholders and directors. Corporations separate ownership and management and there are problems with this system.

As Fulton Sheen wrote:

Those who manage the corporation say they do not own, and they who own say they do not manage. It is extremely difficult under such an arrangement to fix the blame for injustices; the directors blame the stockholders and the stockholders blame the directors. If I own a car I am responsible for its misdeeds. But if ten thousand people had a share in its ownership, the responsibility declines proportionately.

One of the most evident results of this separation is the trend of woke corporations in so-called stakeholder capitalism, which advances the cultural Marxist ideology even to the detriment of share prices.

Companies have pushed woke ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) policies despite being detrimental to the bottom line and therefore violating their fiduciary responsibility to their shareholders. They make the managers look cool and compassionate but the consumers don’t want them and are striking back with damaging boycotts.

The most dramatic example of the “Get Woke, Go Broke” trend is Disney, which has made a concerted effort to be as woke as possible and has underperformed the S&P 500 by over 300% in the last year. More recently, Anheuser-Busch suffered a dramatic 30% drop in profit after promoting transgender influencer Dylan Mulvaney in an ESG campaign.

3. Corporations limit liability altogether

Even when corporations are wholly owned by a single person, making it individually owned and the management and ownership singular, the nature of corporations is to limit—or socialize—liability.

The American corporate system allows the individual to profit from a business venture without fully taking on the risk. Investors in a limited liability company get all the benefits if that company does well, but if that company does some great harm, the individual is protected: capitalized gains and socialized losses. A smoker who got cancer can sue the cigarette company but not the individual investor. For example, none of the CEOs of the major tobacco companies were ever convicted in criminal or civil lawsuits but the Big Tobacco collective had to settle in the landmark United States v. Philip Morris Collection lawsuit.

As Sheen wrote:

Private property has lost much of the connotation it traditionally and rightfully possessed. St. Thomas following the Christian tradition and quoting verbatim St. Basil describes it as potestas procurandi et dispensandi or the power of administration and distribution. As a power it is more than a right: it is a right and also a function, a right for oneself and a function to fulfill for the common good. For Roman law and for Liberalism, property is not a potestas but a jus: jus utendi et abutendi, the right to use and abuse. According to its original and true signification, property was inseparable from responsibility, because it was a personal right inseparable from social obligations. Under Liberalism and monopolistic Capitalism the right to property became divorced from responsibility and its social function.

This is important because the right to own property entails not only the freedom to do with it what you want but also the responsibility to account for it. Responsibility without freedom is slavery, but freedom without responsibility is tyranny.

To really say one owns something, one must have freedom to control it but also the responsibility answer for it.

This isn’t a no true Scotsman fallacy. By definition, corporations are more socialist than capitalist. Socialists and distributists rightly criticize corporations. It’s time that free-marketers and capitalists join them.

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic