In order to know God we first have to understand what God is not. In that same respect in order to understand salvation we have to understand that which leads us away from salvation and God; we call this sin. Our first parents gave humanity the gift that keeps on giving through original sin, none of us asked for this gift from our first parents yet it does not change the reality. The first sin, the fall of humanity came disguised as a gift of knowledge and once Eve succumbed to the temptation of sin humanity’s nature became flawed and no longer in the image of God. No longer could man clearly see the Creator in his reflection except through tainted eyes of the new flawed nature of humanity. As we know not all is lost because of the deprivation of sin because God in His infinite love gave us His only Son and the ability to choose or reject His Son.

“I call heaven and earth today to witness against you: I have set before you life and death, the blessing and the curse. Choose life, then, that you and your descendants may live.” Deuteronomy 30:19

While sin opposes God’s will and can harm or diminish virtues, it cannot utterly destroy human nature. Human free will and Divine grace are not mutually exclusive. God’s grace empowers human beings to choose good, thus maintaining human freedom while also recognizing the necessity of Divine assistance for salvation. Saint Thomas Aquinas eloquently states in his Summa Theologiae, Part I-II, Question 109, Article 2, “Sin is contrary to God’s will. Sin destroys virtues and diminishes other virtues as a result. Sin cannot completely destroy man’s good nature, because that would mean man would not be capable of sin.” Total corruption would eliminate the capacity for sin, which hinges on the exercise of free will, a gift from God that includes the potential to reject Him. This highlights the resilience of the human soul and the enduring presence of free will, even amidst sinfulness. Understanding that we have a choice in sin and we are not predestined to sin but predestined to God and that our sins, if not repented of with a contrite heart, are the very things that can lead to our damnation.

“What I do, I do not understand. For I do not do what I want, but I do what I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I concur that the law is good. So now it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells in me. For I know that good does not dwell in me, that is, in my flesh. The willing is ready at hand, but doing the good is not. For I do not do the good I want, but I do the evil I do not want. Now if [I] do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells in me.

So, then, I discover the principle that when I want to do right, evil is at hand. For I take delight in the law of God, in my inner self, l but I see in my members another principle at war with the law of my mind, taking me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members.” Romans 7:15-23

Acknowledging our sins and turning away from them, a process the Church calls contrition, is crucial for receiving God’s grace. Salvation comes from God’s grace, earned through Christ’s suffering and death, rather than our own actions. Our own actions devoid of God’s grace are more apt to lead us to our damnation. God’s grace helps us share in Christ’s life and slowly heal the image of God in us that sin has damaged. Recognizing our sinfulness and accepting God’s forgiveness are key steps on the path to true happiness, where we ultimately find peace and satisfaction in seeing God. This path involves a partnership with divine grace, leading us to live virtuously, follow the Church’s teachings, and participate in the sacraments, which Christ established as ways to receive grace.

When we explore the consequences of sin we see how it darkens the mind and hardens the heart, making virtuous actions more challenging and sinful desires more overwhelming: “Through sin, the reason is obscured, especially in practical matters, the will hardened to evil, good actions become more difficult and concupiscence more impetuous” (Summa, P. I-II, Q.85 Art. 3). This degradation of the moral faculties illustrates sin’s pervasive impact on an individual’s ability to choose and act rightly. Aquinas clarifies that not all sins are equal in gravity; some are more severe and inflict deeper spiritual wounds: “Our Lord said to Pilate (John 19:11): “You would have no power over me if it had not been given to you from above. For this reason the one who handed me over to you has the greater sin.” and yet it is evident that Pilate was guilty of some sin. Therefore, one sin is greater than another (Summa,P. I-II, Q.73 Art. 2). This distinction between lesser and greater sins indicates a moral hierarchy that affects the soul’s journey toward or away from God.

Exploring the significance of Christ’s Passion as an atonement for human sin, emphasizes the superabundant nature of this atonement due to the love and obedience with which Christ suffered. True atonement for an offense involves offering something to the offended party that is equal to or greater than the offense itself. Christ’s suffering did exactly this, but to an even greater extent: “He properly atones for an offense who offers something which the offended one loves equally, or even more than he detested the offense. But by suffering out of love and obedience, Christ gave more to God than was required to compensate for the offense of the whole human race” (Summa, P. III Q.48 Art. 2).

There are three primary reasons why Christ’s Passion serves as a superabundant atonement: the immense charity from which He suffered, the unparalleled dignity of His life as both God and man, and the sheer scale and intensity of His suffering. This combination makes Christ’s Passion more than sufficient to atone for the sins of humanity, aligning with the scriptural affirmation in 1 John 2:2 that Christ is “the propitiation for our sins: and not for ours only, but also for those of the whole world.”

There is a profound interconnection between human sinfulness, Christ’s sacrificial love, and the divine economy of salvation. Christ’s willingness to endure such suffering, rooted in love and obedience to the Father, underscores the depth of God’s mercy and the pathway to redemption for all of humanity. Aquinas’s explanation in the Summa Theologiae provides a rich foundation for understanding the saving power of Christ’s Passion and its central place in Christian doctrine. Saint Thomas Aquinas observes, “the common folk…were deceived afterwards by their rulers, so that they did not believe Him to be the Son of God or the Christ” (Summa , P. III, Q.47 Art. 5). The populace, misled by their leaders, chose to dismiss Christ, prioritizing earthly authority over divine truth, illustrating how sin can lead to the rejection of Christ’s teachings.

In the Gospels, Jesus’ profound emotional and spiritual turmoil in the Garden of Gethsemane marks a critical point, revealing His deep awareness of the looming sacrifice of His Passion. The Gospel of Luke captures this intense moment of prayer and struggle, where Jesus, fully aware of the impending suffering, submits to the divine will with the words, “Father, if it is your will, take this cup from me; yet not my will but yours be done” (Lk 22:42). The gravity of this moment is further emphasized by Luke’s description of Jesus’s physical manifestation of stress, stating that “his sweat became like drops of blood falling to the ground” (Lk 22:44), an image that powerfully conveys the depth of His agony.

This profound event is intricately connected to the sacrament of the Eucharist, established during the Last Supper. During each Eucharistic celebration, the act of consecration brings about the transubstantiation, making Christ truly present in Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity. This mystical event transcends time, inviting the congregation to partake in the Paschal Feast as if present at the Last Supper. This mystical participation underscores the notion that sin, too, transcends time, contributing to the agony of Christ in His Passion. In Catholic tradition, the Eucharist is more than a remembrance of the Last Supper and Christ’s Passion; it’s a mystical participation in these events. Through transubstantiation, the bread and wine become Christ’s actual Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity making present the sacrifice of Calvary in each Eucharistic celebration, as explained in the Catechism of the Catholic Church Paragraph:1366-1367.

Paragraph 1366 “The Eucharist is thus a sacrifice because it re-presents (makes present) the sacrifice of the cross, because it is its memorial and because it applies its fruit:

[Christ], our Lord and God, was once and for all to offer himself to God the Father by his death on the altar of the cross, to accomplish there an everlasting redemption. But because his priesthood was not to end with his death, at the Last Supper “on the night when he was betrayed,” [he wanted] to leave to his beloved spouse the Church a visible sacrifice (as the nature of man demands) by which the bloody sacrifice which he was to accomplish once for all on the cross would be re-presented, its memory perpetuated until the end of the world, and its salutary power be applied to the forgiveness of the sins we daily commit.”

Paragraph 1367 “The sacrifice of Christ and the sacrifice of the Eucharist are one single sacrifice: “The victim is one and the same: the same now offers through the ministry of priests, who then offered himself on the cross; only the manner of offering is different.” “And since in this divine sacrifice which is celebrated in the Mass, the same Christ who offered himself once in a bloody manner on the altar of the cross is contained and is offered in an unbloody manner. . . this sacrifice is truly propitiatory.”

In Christ Passion we witness the profound suffering of Christ, emphasizing not only the physical pain but also the spiritual agony experienced, especially in the Garden of Gethsemane. Here, Christ deeply felt the burden of humanity’s sins and the impending sacrifice, as detailed in Summa Theologica (Summa, P. III, Q.46 Art. 6). The Bible portrays Christ’s intense prayer and the extraordinary physical sign of His distress, sweating blood, showcasing the dual aspect of His suffering as both human and divine, and the immense weight of sin He carried for humanity.

“Saying, “Father, if you are willing, take this cup away from me; still, not my will but yours be done.” And to strengthen him an angel from heaven appeared to him. He was in such agony and he prayed so fervently that his sweat became like drops of blood falling on the ground.”

Luke 22:42-44

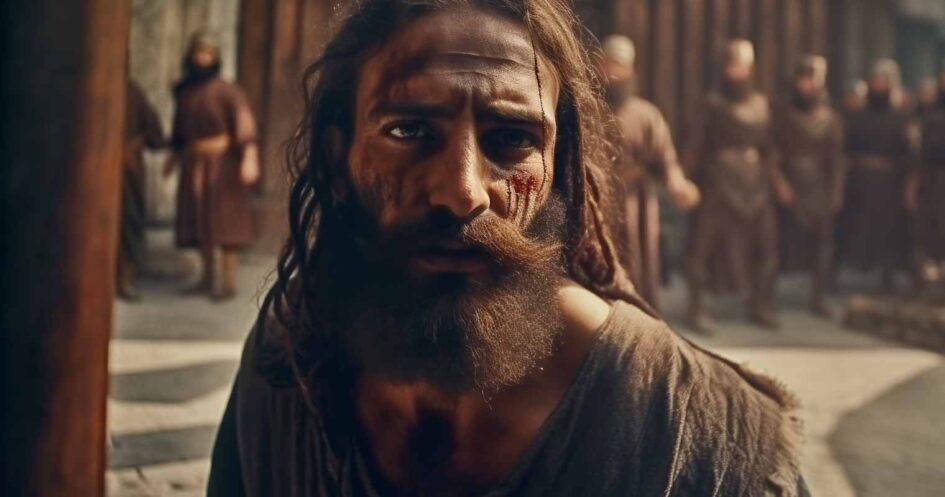

The Passion of Christ, as narrated in the Gospels and corroborated by historical and archaeological findings, encapsulates the profound sufferings Jesus underwent for humanity’s salvation, culminating in His crucifixion at Calvary. This period commenced with His agonizing prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane, where He experienced hematidrosis, sweating blood—a condition indicative of extreme stress. His subsequent trials, brutal scourging, and the harrowing experience of crucifixion underscore the depth of His sacrifice. The Gospels provide a detailed account of these events, from the false accusations leading to His trials to the excruciating pain and humiliation of the crucifixion, designed by Romans to prolong suffering and degradation.

Sin is a grievous offense against God, detrimental to the sinner, severing the divine relationship, and diminishing virtue (Summa, P. I-II, Q.85, Art. 3). Aquinas discusses the varying degrees of sin and their severity, suggesting that our transgressions are intricately linked to Christ’s sufferings, implying that each sin necessitated His atoning sacrifice (Summa, P. I-II, Q.73, Art. 2). This aligns with the Gospel accounts of Jesus’s trials and crucifixion, where He endured immense physical and psychological torment, bearing the collective weight of humanity’s sins.

Aquinas further delves into free will, a divine gift that allows individuals to choose between love and rejection of God. This choice is starkly highlighted in the context of sin; to commit a sin is akin to aligning oneself with those who actively partook in Jesus’s torture and crucifixion. Resonating with the Gospel accounts, this emphasizes the personal responsibility of each believer in the collective narrative of Christ’s Passion, underlining the lasting impact of sin and the perpetual opportunity for redemption through turning towards Christ in love and obedience. Christians need to understand that while Christ’s grace, love, and mercy transcend time, so too are their sins causing Christ’s Passion.

The interplay between Christ’s Passion and theological insights on sin and free will offers a comprehensive understanding of the significance of Jesus’s sacrifice and the role of human agency in salvation. This invites believers to reflect on their own contributions to Christ’s sufferings through their sins and to embrace the sacraments, especially the Eucharist and Reconciliation, as means of grace and reconciliation. The Eucharist, in particular, serves as a constant reminder of Christ’s sacrificial love, urging the faithful to renew their commitment to Him and to reject sin, thus participating in the salvific mystery of His Passion. Through this integrated approach, the personal responsibility of believers within the economy of salvation is highlighted, underscoring the interconnectedness of our actions with Christ’s redemptive act and the importance of aligning our lives with His teachings for eternal salvation.

The echoes of disbelief and denial reverberate through time, with many asserting their goodness or dismissing the transformative power of Christ’s sacrifice. This mindset, which ranges from viewing one’s own flaws as inconsequential to outright rejecting the necessity of Christ, effectively distances individuals from the profound implications of the Passion. The perception of Christ’s suffering and resurrection as mere historical events or intertwined with myth further dilutes their relevance, leading some to overlook the enduring significance of these events in the present day.

Christ’s Passion and Resurrection offers not only a beacon of joyful hope but also a poignant reminder of the weight of our sins. Each act of wrongdoing, in essence, aligns us with the crowds in Jerusalem who cried out for Christ’s crucifixion, deepening His anguish as He journeyed to Calvary. This realization calls us to reflect on the profound personal and collective impact of our actions, urging us to embrace the redemptive power of Christ’s love and sacrifice as a path to true atonement and spiritual renewal.

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic