Writing theoretical essays about abstractions found in philosophy, law or political economy has always been easy, way easier than writing from the heart and making sense of the human experience.

Maybe it’s a different perspective, a different face of that creative spark that comes with a certain genious and more than certain madness that affects all writers, all scholars, all artists. It takes a great deal of energy (and willpower) to try to create without that unexplainable force that comes from within when you finally get inspired or when you find a muse. Or muses. Or simply put, a meaning in your craft.

Life, in that sense, has so many different meanings to every person, that projecting one’s meaning onto others may say more about ourselves than about our inspirations. But sometimes these are not merely projections. Sometimes they are reflections.

I write this now because, unlike many of my other previous essays, but maybe in line with some of my newest ones, I am speaking not as a theorist or an ideologue, but rather as a thinker wandering through his meanderings, putting order in his thoughts as they come by, and building up a meaning as words begin to take shape into phrases.

Muses come and muses go. And so does meaning. We cannot build ourselves up around a person. This is a mistake many people make, and for most of them, it is not a mistake. Smaller lives need smaller causes to make them worth living. This is, by no means, an attack on simpler lives and simpler sources of inspiration. I, myself, have fallen for those from time to time, and I still hope to keep on doing it.

After all, “small is beautiful”, as is titled that amazing treatise on political economy written by E. F. Schumacher. It explores the meaning, diversity and actual incentives that drive economic actors in their natural scale: that of the local community, the family, the town, the guild. Maybe a reminder of a simpler, saner time.

But that does not contradict a belief in a search for grander meanings, for more than peaceful stillness. Life is lived by individuals in small scales, driving their human actions towards satisfying smaller drives and smaller ambitions. Both the economy and society are built upon these principles of scale that could be reminding of William of Ockham’s razor principle, that states that when struggling with two competing explanations, the best one will always be the simpler one.

Life, like everything, also stands on the edge of Ockham’s razor: we live, we love and we choose our meaning in our simplest terms. For some, it works on an utilitarian basis: we live to maximize pleasures and minimize pains. We love to receive love back and we leave when it begins to hurt us. We get inspired by the inmediately available and we try to keep that inspiration around until it fades away.

But some lives also are driven by different principles, by the search of those bigger causes and by giving themselves to abstract ideas in their name. Those lives are the ones of heroes, tyrants, revolutionaries, leaders, artists and all in all, madmen. Or as Thomas Carlyle calls them, “Great Men in History”.

As always, it is my method to compare and contrast ideas, lives, meanings, and by doing so, getting to an organic synthesis of them that concludes the defense of my positions in an understable way. But there isn’t much of a synthesis when it comes to explaining the diving forces of life, society and history, but more of an universal understanding that looks into different scales.

Just as we can take Ludwig von Mises’ Theory and History as an account of the causes of progress from the individual actors in institutional frameworks, each person acting in their interests, forming networks of cooperating and competing interests that drive society into some spontaneously defined goals, we can also take Carlyle’s Great Man Theory as an account of the movement of history as the ultimate show of strength from exceptional individuals who inspire masses into following their personal wills. We could also take Oswald Spengler’s cyclical take on history, that disregards individuals, both ordinary and extraordinary to look at societies, cultures themselves, as living organisms with life cycles that begin, develop, decline and die as time goes by.

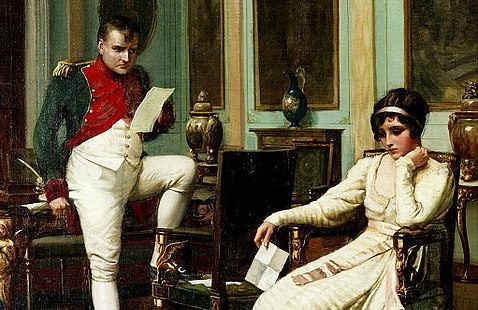

None of those accounts is completely right, and none is wrong either. Just as there was Emperor Napoleon, military, political and administrative genius at the sunrise of the contemporary age, there was Napoleon Bonaparte, tragic husband of Josephine de Beauharnais, whose life outside of her was as big as modern history itself, but with her was probably as small as the one of a cheated military officer, who in her honor and in spite of her tried to conquer the old world just to prove himself as the man we get to remember now.

Do not get me wrong. I like the romantic tragedy of Napoleon as much as the next guy, probably even more than most. There is some sense of familiarity in the lives of great men that I tend to project (or maybe reflect?) on myself. Just like Che Guevara reminds me of my fighting, radical spirit when the place I come from calls me back in their crisis, Napoleon reminds me of my own personal tragedies as I rise above my circumstances and become better. As I get to become who I’m meant to be.

My life seems dirven by a clear desire to become one of those Great Men in history, but my emotions keep reminding me that I’m still bound to human action on the smaller scale, with natural inclinations to the simplicity of love and certainty that greatness cannot provide. Greatness is a dividing substance: it makes you choose between the heroic, romantic tragedy of transcendence, and the peaceful stillness of an unchanging present, or at least the belief of such stability.

Some of us have a choice, some other do not. Our lives correct course as they go by and we naturally incline towards our most natural paths. Napoleon and his progeny could not live up to mantain their greatness in time, but their legacy lives on in history. The Capetians, on the other side, managed keep a hold on time for their benefit, just to let history fade them away into the unknown.

But even in such crucibles, even in periods of transition, when we get to choose between greatness and stillness like the ones I now struggle with, there seems to be a single thing that remains untainted by instability and the mortal edge of history: love.

Love seems to be the definitive emotion, the ultimate meaning in life. It is not because of my own conservative affinities that I would quote Roger Scruton by saying that it all reduces itself to “the disposition to hold on to what you know and love”, to the preservation of that inspiring meaning that holds the small platoon small and tight, like an unbreakable unit.

But just like everything else, love is also a changing substance, one that cannot really be held tightly for the risk of tainting it with pressure and external toxins. Love, just like water, needs both stillness and orderly flow so it keeps fresh and keeps on bringing life. Disorderly, untamed, unhinged love brings up pain and destruction, just as heavy rains can flood crops and hurricanes can destroy towns.

I think of some of my friends at this point, like Vilma. Her Substack, The Contrary Mary, keeps a personal, irreverent and ultimately personal take on the mundane and the transcendent just as only a fellow traveller in this mess called life and history can be. My writing tends to be more messy, mixing esoteric academic knowledge with personal experiences in what looks half a personal diary and half an unfinished manifesto. But Vilma always finds a way in her writing. Maybe it’s the relatively bigger life bagage with struggles and hopes and dreams that comes from her childhood to her current age. Or maybe she just takes things less seriously than me and lives more happily.

I also think about my friend Zosia and her interest in logotherapy. Before talking to her, I had a very vague knowledge about Viktor Frankl and his book Man in Search of Meaning. But as I met her, I got wondering: what kind of meaning can be found in lives connected through the most unexpected networks? Because it would be natural for lawyers to meet in a public interest advocacy group, but not to bring up an unwilling global citizen like me with an academically trained mathematician like her in such a group. Maybe we all create our meanings in life through the love in our causes, the passion in our beliefs.

And then comes history. I try to stay authentic. Or rather, to find my authencity in what I do. I struggle to find and define myself outside of certain structures, like my family, my academic studies or my failed loves. I don’t define myself through my current job and I have never defined myself through my social networks. But my identity as a person still remains to be found. I try to bind myself to higher causes. Reform, freedom, tradition, revolution and counter-revolution. But maybe I should try to define myself through love, specially after having felt what defining me in pain did.

Love is more reliable than other principles. It is closer to the transcedentals of the True, the Good and the Beautiful. But not a smaller, personal love, since those are also unreliable. A grander love, a love for the human experience in its fullest. A love that reflects God’s creation in the quest for meaning from the individual to the universal scales.

A Great Man in History built from and through love.

We already had Christ as such an example. God Incarnated. Divine love in human flesh. It is hard to surpass that. Well, it is certainly impossible. It is the struggle to assimilate ourselves in that that would make us saints.

But sainthood is also tricky. Nowadays it depends on a full administrative procedure that the Roman Curia controls tightly. Maybe it is in our best interests to become more like private saints, saints to God, saints to ourselves, to our local communities, to our loved ones.

Sainthood, like love, or greatness, is indeed a struggle, and like all other struggles, it is a transition. It makes us move from one point to the other, from one state to the next. It changes us. But as Ezra Pound put it in his Pisan Cantos, it is also still. It keeps us in what we were and we will be.

“What thou lovest well remains,

the rest is dross

What thou lov’st well shall not be reft from thee

What thou lov’st well is thy true heritage”

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic