When it comes to Constitutional Law, most countries tend to follow a similar pattern, or at least, a similar institutional design, derived from the Western political tradition of separation of powers, where both Locke and Montesquieu’s models are applied.

In practice, these means that almost any country on Earth will have some similar institutions in its political governance, and aside from the well-known Executive and Legislative branches pretty much all governments have, there is usually a Judiciary, constitutionally enshrined to judge and apply the respective laws of the country, with a particular interest in directly applying, or at least making their respective supreme law, their Constitution, be respected in their proceedings, following Hans Kelsen’s theory of constitutional supremacy.

For that reason, the separation of powers political model usually grants its highest Judicial institution, normally a Supreme or National Court, the powers for interpreting the political Constitution of the country that follows this model, and to make court rulings and judgements in base of its articles and rules.

By default, and most especially, by its institutional prestige, the Supreme Court of the United States is seen as a blueprint for other countries when constitutionally designing their own Judiciary, and in turn, this influences the way foreign Supreme and National Courts works and the way these foreign justices interpret their own constitutions, with a famous quote by Alexis de Tocqueville describing that even if “the representative system of government has been adopted in several states of Europe”, he was “unaware that any nation of the globe has hitherto organized a judicial power in the same manner as the Americans […] A more imposing judicial power was never constituted by any people.”

Ecuador, of course, is no stranger to this model, and even if it does not follow it formally, time has proven its highest constitutional (and some would say even political) institution, the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, has fallen into the same pattern as other High Judiciaries inspired by the American Constitutional model.

With this in mind, it should be useful to consider the way American Constitutional Law and the American Constitutional interpretation doctrine could be helpful to understand the constitutional power and legal dynamics of the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, engaging in a comparative analysis between American and Ecuadorian Constitutional Law.

Similarities and differences in the constitutional design of the Supreme Court of the United States and the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court

For this reason, when comparing the institutions of two countries, the first tool one must use are its laws, as they present, in a descriptive way, the foundations on which they are built, and the objectives they seem to stride for.

For instance, the Supreme Court of the United States got to be established by the US Constitution in Article III, section 1, that disposes that “the judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish”, arranging in section 2 that “the judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority”, whereas the Ecuadorian Constitution does not follow the same standard, and instead of establishing its supreme judiciary as its flagship institution for constitutional justice and interpretation, it creates two different judiciary entities, one as a high appeal court or court of cassation, called The National Court of Justice, as ruled by articles 178 and 182 of the Ecuadorian Constitution, and another as a “supreme body for controlling, constitutionally interpreting and administering justice in this matter”, called the Constitutional Court, as declared by article 429 of the same Constitution.

In practice, this means that in the US legal system, the judicial review power to determine whether a legislative act of Congress is constitutional, as described in theory in Federalist No. 78 by Alexander Hamilton, is very much diffused into the decentralized inferior courts established by Congress, and then concentrated into the Supreme Court, given its quality as supreme, its original jurisdiction for all cases in which the State is Party and its appellate jurisdiction for all other cases.

However, for the Ecuadorian case, this key distinction between the Judiciary itself and the Constitutional Court as a separate, independent institution makes judicial review, here known as constitutionality control, directly concentrated by the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, which has, ultimately, under an analogous judicial review, the total and final control of all acts produced by government officials in all branches, including the very Judiciary, as well as the Executive and Legislative, as described by articles 440 and 436, respectively, of the Ecuadorian Constitution.

Some similar elements between the Supreme Court of the United States and the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court are, for example, that both institutions exert some kind of judicial control over the acts of other government branches, and most importantly, that both are currently composed by 9 magistrates, as disposed by the US Judiciary Act of 1869, signed by President Ulysses S. Grant, and by article 432 of the Ecuadorian Constitution.

Nevertheless, the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court still has more similarities with other institutions in comparative constitutional law, such as the French Constitutional Council, than with the Supreme Court of the United States, as both the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court and the French Constitutional Council are constitutionally empowered to make interpretations of the fundamental meanings of their constitutions, legislation, and treaties, to potentially declare dispositions of laws and treaties to be contrary to their respective Constitutions or to principles of constitutional value deduced international treaties, rendering these laws and treaties invalid if declared as unconstitutional.

These similarities between the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court and the French Constitutional Council go as well as by being filled by nine magistrates (another similarity with the Supreme Court of the United States) who serve non-renewable terms of nine years, one third of whom are appointed every three years by political representatives of the Executive and Legislative branches of government, as established by articles 432 and 434 of the Ecuadorian Constitution and French Ordinance 58-1067 of 7 November 1958, the organic bill that rules the structure of the French Constitutional Council.

Nonetheless, even if there seems to be a greater difference between the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court of the United States, a comparative assessment between the two is valuable, since the judicial review powers both institutions have are influenced by pretty much the same constitutional interpretation doctrines, as we will see in the next section.

The same pattern in constitutional interpretation and ideological leanings?

Given the institutional design of both the Supreme Court of the United States and the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, as well as it regulated composition and its constitutionally granted powers of judicial review and constitutionality control, some comparisons can be easily drawn between the two, and most particularly in the ideological leanings of its magistrates and justices when it comes to constitutional interpretation.

First of all, both Courts are composed by 9 sitting judges, and currently, these are Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate justices Clarence Thomas, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett for the Supreme Court of the United States, and Hernán Salgado, as President and Teresa Nuques, Agustín Grijalva, Ramiro Ávila, Alí Lozada, Daniela Salazar, Enrique Herrería Bonnet, Carmen Corral and Karla Andrade as sitting magistrates for the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court.

The Supreme Court of the United States is known to have two distinct, ideologically factions in its composition, often described in basis of a conservative/liberal division in personal political leanings, usually according to the US President that has appointed each SCOTUS Justice, which in turn reflects, respectively, a ‘dead-constitution’ originalism or ‘living-constitution’ activism divide in the constitutional interpretation doctrine espoused by each of them.

As of now, the Supreme Court of the United States is composed by three justices appointed by Democratic presidents: Justices Breyer, Sotomayor and Kagan, who would be its liberal wing, and who all have a strong record of activist opinions, both majority and dissenting, and by another six justices appointed by Republican presidents: Chief Justice Roberts and associate justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, who would be its conservative wing, although with Roberts, Alito, Gorsuch, and sometimes Kavanaugh as more moderate, siding often with majority opinions, and Barrett and most especially Thomas as more radical, usually writing dissenting originalist opinions.

On the other hand, the current composition of the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court is also known to have two distinct, ideologically factions, not exactly described in the same line of the conservative/liberal divide that would reflect the same ‘dead-constitution’ originalism or ‘living-constitution’ activism split of the Supreme Court of the United States, but closely resembling that very same model, although with a reversed trend.

For instance, the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court textualist faction would be composed by President Salgado, and judges Nuques, Herrería Bonnet, Corral, with both Salgado and Corral filling in for Clarence Thomas position as the often-dissenting originalist in the Court, and Herrería Bonnet as more moderate, and its so-called ‘garantist’ and ‘progressive’ faction would consist of judges Grijalva, Ávila, Lozada, Salazar and Andrade, with Ávila and Salazar filling in for Sonia Sotomayor’s position as the most activist judges, considering they have drafted some of the most controversial majority opinions of the Court in cases such that ruled on the constitutionality of cannabis recreational use, same-sex marriage, abortion and the criminality of teenage consensual sexual relations.

Of course, a similar constitutional interpretation trend tends to be shared by the respective factions in the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court of the United States, with conservative and originalist judges often making textual, by the rule interpretations of constitutional dispositions, claiming that the Constitutional text is clear enough for its direct application, and with liberal, progressive and activist judges making pompous interpretations that incorporate some kind of ideological charge, often as a guarantee of human rights or as some kind of result of the development of the meaning of rules in a changing society in what is called either living-constitution constitutionalism in the US or rights’ progressivity in Ecuador.

Some final remarks

In the end, this situation can be interesting as it is useful, for it explains certain dynamics in the way Supreme and Constitutional courts all over the world can be politically influenced when exerting judicial review and interpreting the Constitutions of their respective countries, as it is a trend that can already be proven when comparing the American and Ecuadorian case for their Supreme and Constitutional courts, respectively.

As this is merely an introductory essay into this topic in comparative law, any scholarly analysis of the design and ideological leanings of both the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as many other similar institutions, such as the French Constitutional Council and the Polish Constitutional Tribunal would instantly become a significant legal contribution for the law of both countries, and it could ultimately prove that there is either some natural inclination to ideological divide in any High court with judicial review powers, or that the American influence in foreign law is strong enough to export its ideological divide into the Judiciaries of other countries when their Supreme Court design is used as a blueprint for their Constitutional Courts and Tribunals.

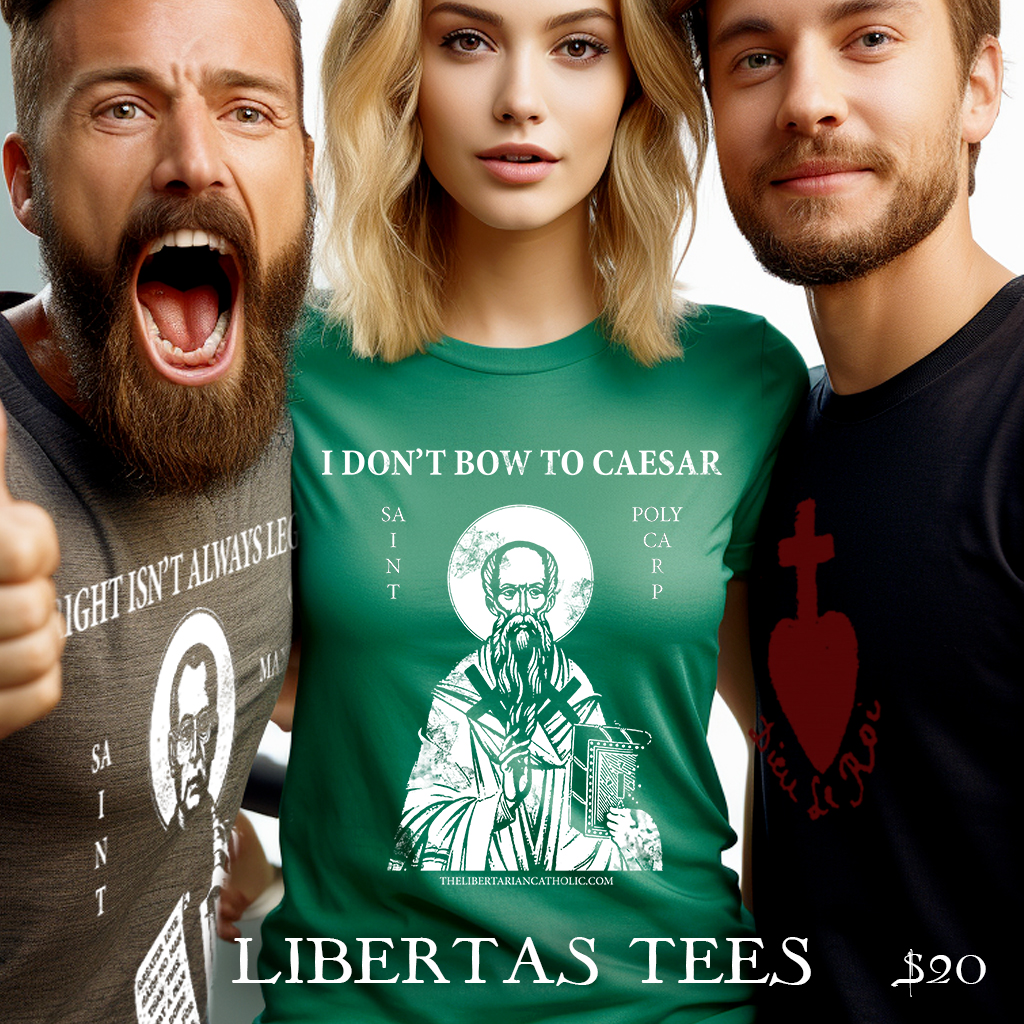

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic