Amid Eastertide, there might not be a better time for the faithful and curious alike to immerse themselves in the profound narrative of Christ’s life, passion, and resurrection. While the chic option these days is the indie series The Chosen, moviegoers shouldn’t forget the first life of Jesus television series, Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth, which is by all standards superior to the later production and still serves as the quintessential cinematic portrayal of Christ to this day.

Not only was Jesus of Nazareth a landmark in 1977 when it first aired, quickly eclipsing Nicholas Ray’s 1961 King of Kings and George Steven’s 1965 Greatest Story Ever Told, it has remained relevant to this day with subsequent productions like Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ and Dallas Jenkins’ Chosen failing to reach the narrative heights of Zeffirelli’s epic.

While all portrayals of Jesus will have their critics, especially when it comes to Scriptural interpretation, it is constructive to assess the picture on artistic merit alone. And, by that criterion, only one stands out as a masterpiece.

The production of Franco Zeffirelli’s “Jesus of Nazareth” was a groundbreaking and controversial endeavor from the start. It began with a suggestion from Pope Paul VI. The success of Lew Grade’s “Moses the Lawgiver” miniseries in 1974, which was noted for its liturgical verve, caught the attention of the Pope, who recommended Zeffirelli as the director for a life of Jesus series.

The production team was a motley crew. Lew Grade was a Jew, Zeffirelli was rumored to be homosexual, and scriptwriter Anthony Burgess had recently raised eyebrows with his scandalous Clockwork Orange, not quite the trinity one would expect to produce a reverent piece on the story of Christ. To make matters worse, Zeffirelli had been quoted as saying that he hoped to portray Jesus as “an ordinary man—gentle, fragile, simple,” which led Fundamentalist Christian pastor Bob Jones III to decry the film as blasphemous without even seeing it.

Of course, it is not blasphemous to depict Jesus as a man since He was fully a man. He was also fully God, but that is not as easy to portray in film. Striking a balance between the two would prove to be the central challenge in the project, and its crowning achievement.

The Direction

As Pope Paul VI had intuited, there could only be one director for this picture. With Florentine paintings and opera flowing in his veins, Zeffirelli’s instinct was, as he called it, “lavish in scale and unashamedly theatrical”. Zeffirelli transforms each storyboard frame into a living, breathing work of art, making the miniseries a visual feast. Every shot resembles a timeless painting, from the serene beauty of the Nativity to the haunting poignancy of the Pietà.

The actors bore much of the burden. As Robert Powell noted, “We’ve had sand blown in our faces by a wind machine and incense filling our lungs on numerous occasions. Franco wants to give the picture a feeling of age, like the old Italian paintings.”

Zeffirelli is nothing if not sumptuous and visceral. Many will recall Romeo and Juliet’s intense fight scenes almost as if they took part. The viewer experiences much of the same intimacy here, in the Nativity childbirth, the Fishes and Loaves, the Adulteress, and the Passion scenes. It is no doubt the expertise with which Zeffirelli captures the visceral that he must forgo what might have seemed like essential episodes—the first miracle at the Wedding at Cana, the Temptation by Satan in the desert, and the Transfiguration.

The Script

The duo of Franco Zeffirelli and Anthony Burgess pack a powerful screenwriting punch, seamlessly weaving together the scriptural accounts with a natural, accessible language that amplifies the impact of Jesus’s words.

Throughout the miniseries, Burgess and Zeffirelli favor the colloquial over the poetic, resulting in some of the more poignant exchanges between the characters. However, this approach also leads to a few questionable interpretations of Jesus’s teachings. In the scene about the “constantly changing” law, for instance, Jesus’s words border on rebellion, and his exhortation to “Open your heart, Judas, not your mind” has a quasi-20th-century esteem psychology quality to it.

But even with these misfires, the dialogue is exquisitely crafted. Beyond the brilliant parables and teachings from Scripture, we get some of the best lines in all of film:

The rabbi to Joseph: “Women are the loveliest and brightest of God’s creations. And thank You God, I am a man.”

Matthew explains to a disconsolate Simon Peter: “You’ll never fish again. You’ll never get drunk again. And you’ll never go back to Capernaum again. None of us will. We’ll never be the same. And neither will the lives of everyone in the whole world. We know why, Simon. We’re the first to know.”

And in the final scene when Peter begs Jesus, “Oh Lord, stay with us. For the night is falling, and the day is all full.” Jesus replies, looking directly into the camera, “Don’t be afraid. I am with you everyday until the end of time.”

The nature of the sprawling storyline allows it to incorporate a diverse range of storytelling approaches. The result is a tapestry of story, part courtroom drama, part mystery, suspense, coming-of-age, buddy film, and multiple love stories. Altogether, it is no question that the narrative amounts to nothing less than the “greatest story ever told.”

The Narrative

The narrative genius of Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth lies in its ability to bring the Gospel to life with meaningful drama and accessible language, while also showcasing some of the most inspired performances in cinema history. Zeffirelli’s approach was to convey the immaterial through the material by incorporating historical context, providing character foils, and combining historical events for greater impact.

The script, co-written by Zeffirelli, Anthony Burgess, and Suso Cecchi d’Amico, is a masterful Diatessaron, a blend of the Gospel accounts with artistic license, creating a tapestry of moments that feel both familiar and revelatory. The miniseries is not just a visual spectacle; it is an emotional and spiritual journey that invites reflection and introspection.

One of the most powerful examples of this is the scene where Jesus attends the tax collector Matthew’s party against Peter’s wishes and recites the Parable of the Prodigal Son. Separated from the event, the parable is meaningful but limited in effect. Here, it takes on new impact, applying to both Matthew (the prodigal son) and Peter (the older brother). The scene is a masterclass in storytelling: As the viewer witnesses both Peter and Matthew undergoing a conversion upon hearing Jesus’ words, the viewer too experiences a kind of conversion.

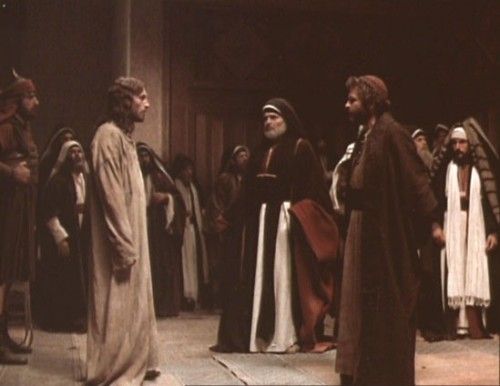

The inclusion of historical and fictional elements in the miniseries adds layers of meaning and enriches the story, providing context to Jesus’ impact in his time. The struggle for independence by the Zealots, the cultural/political balance sought by the Sanhedrin, and the Roman quest for order are all explored, elevating the narrative to sublime heights.

This is true primarily with regard to the completely made-up character of Zerah, who serves as the primary villain and who masterminds the plot against Jesus. While traditional accounts paint Judas as the greedy sneak, betraying Christ for money, this account makes Judas an idealist, first trying to convince the Zealots that Jesus is their Messiah, and then working with Zerah and the Sanhedrin to encourage Jesus to prove himself. Not only does this device make for better villains (a villain who is foolish or unrelatable is no villain at all), so too does it bring to light the gravity of Jesus’ actions in Jerusalem. As Jesus overturns the money tables, calls out the Sanhedrin as hypocrites, and boasts of his ability to raise the temple in three days, we watch as a frustrated Judas frets over the lost opportunity, giving him understandable frustration and relatable motive.

The Cast

The cast and acting in Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth are unparalleled in any other life of Christ and perhaps in any other film ever. The miniseries boasts a stellar ensemble of actors who are not only renowned for their craft but also able to deliver nuanced performances without overacting in an attempt to steal the show.

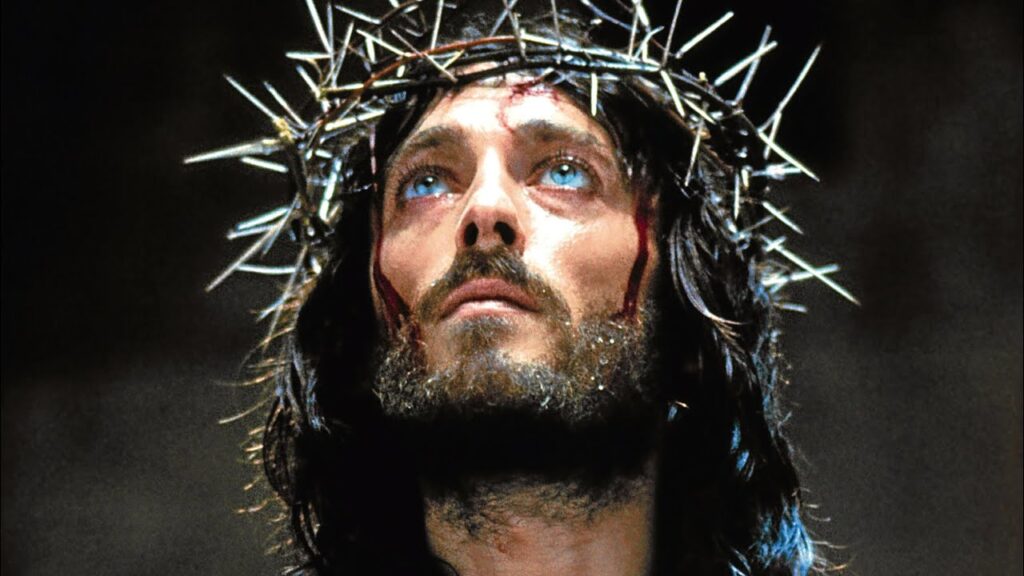

Robert Powell’s portrayal of Jesus is nothing short of awe-inspiring. Modern critics can’t get over the fact that Jesus has blue eyes, though anthropologists have concluded that it’s not outside the realm of possibility. But to dwell on such a detail is to miss a ground-shaking performance. It is said that he was chosen over Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino because he more closely resembled Warner Sallman’s Head of Christ. He also fits the profile of the image on the Shroud of Turin to no slight degree and was an exact 31 years of age when filming started and 33 when it was released. Whatever the reason, it was an impeccable choice. Powell mixes a sense of serene divinity with a fierce humanness that it is difficult to imagine even greats like Hoffman or Pacino pulling off. His gaunt features fit the image from tradition, especially during the Passion and Crucifixion, during which Powell said he ate nothing but cheese for two weeks to arrive at the appearance. The performance was so convincing that not a few have claimed it as a central driver of conversion, including the actor himself. In an interview after the show’s release, Powell revealed that his experience learning about and understanding Jesus made him come to believe.

Other cast members offer similarly moving performances, even if they are not as life-changing as Powell’s. Several standouts are worth mention: Twenty-six-year-old Olivia Hussey is a convincing teenager Mary and also a weathered mother of the crucified Christ. Peter Ustinov is the perfect ancient villain, having played Nero in Quo Vadis, the slave trader Batiatus in Spartacus. Here as Herod I, Ustinov is perfection. Christopher Plummer and Valentina Cortese deliver a dynamic duo as Herod Antipas and Herodias.

James Mason as Joseph of Arimathea and Lawrence Olivier as Nicodemus are brilliant in their portrayals of the sympathetic members of the Sanhedrin, yearning for truth. Michael York’s performance as John the Baptist is a burst of visceral energy, reminiscent of his portrayal of Tybalt in Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. Anne Bancroft’s unvarnished portrayal of the repentant Mary Magdalene is a poignant and powerful addition to the cast.

Ian McShane’s portrayal of Judas is a tour de force in character development, revealing Judas as an idealist who first tries to convince the Zealots that Jesus is their Messiah and then works with Zerah and the Sanhedrin to allow Jesus to prove himself. Ian Holm’s portrayal of Zerah, a fictional character who serves as the primary villain, is as close to a Satan as this picture—or any other for that matter—presents.

The only real let down is Rod Steiger’s Pontius Pilate, who, as it is with most Passion portrayals, is annoyingly impatient and short-tempered. Steiger is forced to convey a complicated situation by emoting, which he must have well known is the least effective way of evoking emotion. As a result, one of the most important scenes in any life of Jesus, Pilate’s interrogation with Jesus, though serving its purpose, is perhaps the greatest missed opportunity in the film.

The Broadcast

Jesus of Nazareth was broadcast first in Italy in March and April 1977. Pope Paul VI endorsed the program Palm Sunday, April 3, 1977, before the airing of the second episode and called on his listeners to view it. The miniseries was a cultural phenomenon in Europe and America, with some 50% of viewers tuning in to watch the series. Nielsen ratings calculated that the series, which had been the most expensive television production at that time, garnered over 200 million viewers on its first broadcast.

Zeffirelli sensed from an early age that his role as filmmaker would culminate in this picture. In a later interview, he said he realized “the weapon I had in my hands and how it could be decisive for the lives of thousands of people, as much for good as for evil.”

“I only did what I could do as the Christian that I am in the depths of my spirit,” Zeffirelli said.

After the picture’s release, Zeffirelli recalled that the Pope received him in a private audience to express his appreciation for the accomplishment. “When Paul VI received me in a private audience after viewing the film in 1977, he thanked me and asked me what the Church could do for me. I told him: ‘I would like this work to be brought to Russia as well.'”

“He looked at me and told me prophetically: ‘Have faith; soon the flag of Our Lady will wave above the Kremlin, in place of the red one,’” he recalled.

And, with a touch of artistic license, Zeffirelli noted that, “On Dec. 8, 1991, the feast of the Immaculate Conception, the red flag with the sickle and hammer that waved above the Kremlin for decades was replaced with the Russian Federation flag.”

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic