Everyone in contemporary right-wing discourse, and by everyone, I mean most informed, if not well-read, intellectually driven people, is aware of the current explosion of schools of thought in the Catholic, and overall Christian, political tradition.

I, myself, wrote about this phenomenon years ago, in my piece titled The Fifth School and the Nominalist Trap, where building upon Ross Douthat’s essay for First Things, Catholic Ideas and Catholic Realities, and his classification of modern Political Catholicism in four different categories: Populists, Integralists, Benedictines and Tradinistas, I added a fifth one, that of anarcho-traditionalists, before arguing against such a categorization, in the sense that it adds up more to the internal divisions within the Catholic Church than it expands its intellectual diversity.

Now, years later, having come around, and in a much different position, both personally and intellectually than when I first wrote that piece, I want to review it in the light of the latest developments in Church, State and society, as well as in consideration of the overarching influence of a very particular group of intellectuals in such developments.

The first point, in that sense, is that there ultimately was not a division in the way Douthat put it at the time. Yes, there is still a certain diversity of opinions in the Catholic intellectual sphere, but discourse has been dominated for the last two years by the integralists, or as they call themselves, the Postliberals.

This ragtag group of intellectuals, headed by Harvard Law Professor Adrian Vermeule, Notre Dame political theorist Patrick Deneen, CUA theologian Chad Pecknold, journalist and author Sohrab Ahmari, and former UDallas, now Hungary-based scholar Gladden Pappin, has become the main circle around which a certain brand of religious political ideas orbit, and half of the time, their takes are not even religious, but merely practical, more-than-conservative takes on governance, foreign policy, law, public morality, economics and general politics.

They are not alone, though, and as their Protestant counterparts in the Anglophone world, a loosely associated group of so-called Christian Nationalists has risen as well. Spawning from the old Christian Right, and further emboldened by the presidency of Donald Trump, as well by its rather theatrical fall, Christian Nationalism has become somewhat of a staple in current American politics, a Grim Reaper of sorts, a ghost of generic ‘fascism’ scaring gullible liberals and progressives with mere theory and nostalgia for a past long gone and a future lost.

Both Integralists and Christian Nationalists are more of a niche intellectual exercise back in the United States, where their influence is mostly due to the cultural pipeline from high academia towards establishment-compliant, Cathedral-affiliated publications, before streaming down to social media and to grassroots communities.

In a sense, it is no longer ‘cool’, or fashionable, to be just another neolib-neocon promoting free markets, hawkish foreign policy (except when it comes to Russia, or the Middle-East) and whatever abstract ‘values and principles’ you can find and interpret from the US constitution. These institutions in the neolib-neocon network still hold all the necessary resources for young aspiring bureaucrats and secular clerics to make themselves a name in DC (or even Brussels, as it also happens in Europe), so our punk-ish religious radicals still tolerate them as part of the necessary means to achieve their goals.

Speaking of goals, those are certainly not yet clear, as it was very well stated in Patrick Deneen’s new book, Regime Change, which aside from further exploring the same repeating critiques of the current American (and global) governance, does not really define the ultimate direction, or ways, this ideal Christian state will be implanted.

What is clear, however, is that both integralists and Christian nationalists are very much inspired and aligned by two practical examples of policy being currently applied on the other side of the Atlantic: those of Poland and Hungary, which led by right-wing governments for the last couple years, have undergone deep internal changes that seems to have become the blueprint of what their intellectual counterparts want to do in the US.

It is no secret, of course, that Hungary is actively trying and attracting intellectual talents from abroad to enrich their own universities and specially, its ‘royal’ court of experts surrounding Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. Aforementioned Gladden Pappin, as well as former ‘Benedictine’ and conservative polemist Rod Dreher, as well as other important figures in right wing discourse such as IM-1776’s founder Mark Granza and part of the staff of The European Conservative are now based in Budapest, and even if their role is rather marginal, the growing environment for conservative discourse, promoted and protected by the Hungarian government is becoming very apparent in their policies, and it seems to be also working to keep the ruling Fidesz party in power.

A little further up north, in Poland, a similar situation is also happening, but without the mediatic reach Hungary is getting. The new Poland, built upon Lech Wałęsa’s Solidarność, economically integrated to the most efficient elements of the European Union´s economy, and kept in a certain growth path by the now polarizingly opposed conservative Law and Justice and center-right liberal Civic Platform, is becoming even more of a powerhouse than Hungary, but without all the fuzz.

Unlike their Magyar partner in making the EU uncomfortable for their legal challenges to progressive impositions from Brussels, Poland does not get the same interest American right-wing figures have given to Hungary, but it compensates with a much different internal organization that does capture its internal, national, and certainly very Catholic, spirit better.

The way I see it, Hungary seems like a sandbox for integralists and Christian nationalists with its ‘direct rule’ from Budapest into the mostly rural surrounding counties, whereas Poland means the practical approach to a more complex application of right-wing policies, with a highly decentralized country with a strong civil society, and most importantly, with an organized internal opposition than can actually disrupt the Integralisr/Christian Nationalist project in every electoral opportunity, as it recently showed in the last general election.

The Polish take is also different, as it its not merely attracting useful foreign conservative talent, but just foreign talent (as well as foreign labor in general) for their own growth. A sort of ‘open nationalism’, if you will, as long as you try to integrate as much in the internal Catholic culture, or at least you don’t become a burden to it. Or at least that’s how it used to be under the Kaczyński-led regime.

Now, what does anything of what has been stated has to do with the title? How does all of this relate to a counterrevolutionary Neapolitan movement from the Napoleonic ages? Wouldn’t a “new” Sanfedism just means something strictly tied to the Italian Mezzogiorno?

In a sense, yes, it does, and while there a certain marginal streak of traditionalist monarchists in the south of Italy calling for the restoration of their Bourbon sovereigns (they are also divided between competing pretenders, and both of them are rather liberal, with Pedro de Calabria as a supporter of his cousin Felipe of Spain’s crowned republic, and with Carlo de Castro as a regular presence in international organizations such as the UN’s ECOSOC Council), I do not think there is a possibility for ‘true’ sanfedismo to be reborn in the former Two Sicilies.

My take, thus, is to reconsider the basic tenets of Sanfedism as it was organized by Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo during the French Revolutionary Wars, and see how much of these can be reflected in American Catholic Integralism an Christian Nationalism and their European darlings, Hungary and Poland.

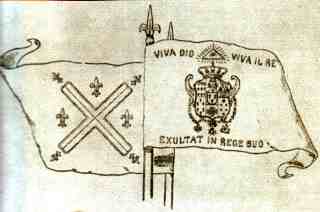

In its most strict definition, Sanfedismo was the name of the popular uprising against the French Revolutionary client state in Naples, the Partenopean Republic, under the ‘spiritual’ protection of Cardinal Ruffo, the support of British agents, including Lord Acton’s ancestors, including clerics, bandits, brigands, and peasants, and loosely confederated in the name of the ‘Armata della Santa Fede in nostro Signore Gesù Cristo’, Italian for ‘Army of Holy Faith in our Lord Jesus Christ’.

So far, just another classical reactionary and counterrevolutionary movement in the same line as Carlists in Spain, Miguelists in Portugal, Legitimists in France, Jacobites and later High Tories in Great Britain, and let’s say it, even Loyalists in North America and Cristeros in Mexico.

It is, nonetheless, the name that really rings a bell for me, notwithstanding the obvious religious inspiration and direction: ‘Army of Holy Faith in our Lord Jesus Christ’. Army. Holy Faith.

Our ‘New Sanfedists’, do liken themselves into an intellectual and cultural army of the Christian faith. Some Catholic groups, like the American TFP (Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property), as well as its overseas counterparts, including the Polish conservative think tank Ordo Iuris, fashion themselves in terms of cultural militance based on Christian principles.

Other organizations belonging to the same networks, such as Hungary’s Mathias Corvinus Collegium, or the American-based Alliance Defending Freedom advocacy group (and its global branch, ADF International) are also involved in the culture wars against progressivism, confronting the liberal-democratic establishment in by any institutional means available, let it be education, courts or parliaments.

Whereas the Hungarian approach is not as explicitly Christian as the Polish one (let’s remind ourselves that the last Polish Justice Minister, under the former Law and Justice government, Zbigniew Ziobro, explicitly endorsed Catholic integralism and Christian morality in his proposals for judicial reform), or as it could be the American one in some of its elements (let’s think of J.D. Vance or Marjorie Taylor-Green), it is still Hungary, more than Poland, the go-to example of the Postliberal Cardinal Ruffos on Substack, and, it is Hungary that attracted Tucker Carlson, not Poland.

Even as it may sound romantic to think about Sanfedismo in its historical form, it was not the self-immolating counterrevolution one would have expected: after restoring King Ferdinand to the throne in 1800, the movement was quickly dissolved (except its criminal elements, that later became anti-Savoyard briganti, and still survive up to our days, rather secularized, as the titular Mafia, and the local Camorra, ‘Ndrangheta, and Sacra Corona Unita varieties in the southern regions of Italy), and Cardinal Ruffo remained an important diplomat and officer, brokering deals both with and for Napoleon, the Holy See and his former Bourbon sovereigns.

Neosanfedism will probably follow the same path, as its lower, less prestigious elements will keep further radicalizing into militant groups that may end up becoming desacralized themselves, while their intellectual vanguard continues pontificating from their ivory towers as regimes come and go.

If Cardinal Ruffo could transition from leading forefather of a fanatic reaction against Jacobinism to a skillful agent in service of the different powers of his time, ultimately not serving his faith but its institutional church, then why would his contemporary equivalents do otherwise now, when they can play the academic and political games as long as there is someone to serve?

I am, by not means, attacking nor criticizing the marvelous work these intellectuals, as well as many other organizations do and have done for the larger Christian cause in Western politics. But as a rather self-reflecting conservative, I do understand that sanfedism, just like neosanfedism, will be nothing but a spasm in the constant progress of history towards entropy.

Maybe it’s the natural pessimism common to all conservatives, albeit thinly disguised as reverence for tradition, that unite us together: we struggle to keep the fire of the past alive because we fear a future that always keeps on showing as increasingly dark.

I keep and will keep on checking and cheering on the developments of our neosanfedist co-idearies as much as I can support the causes of my fellow paleos and any other bona fide conservatives, but I cannot help but wonder where, if somewhere, anything of this is actually leading us.

Sanfedism did not stop the changes in Italian political history that ultimately led to a rather counterproductive unification, and I am fairly certain this neosanfedism will not restore virtue to the American polity nor to its satellites in Europe, even if some of them actually show some success.

But for this kind of conservative pessimistic leaning, there will be further occasions to discuss at length.

For now, we can only try to place ourselves in a hypothetical timeline as we wait for the next Napoleon to cement the victories of the Revolution with his sword at hand, no matter how many sanfedists or neosanfedists confront him.

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic