Christian theology is in crisis. According to theologian Peter C. Phan, forces internal and external to the Church have culminated to a point where “drastically divergent answers are given to such fundamental issues as the nature of God, the role of Christ, and the mission of the church, even in churches known for their insistence on uniformity and orthodoxy such as the Catholic Church.” The explanation of and response to this crisis is offered in Stephen B. Bevans’ even-tempered and insightful study, Introduction to Theology in Global Perspective.

The reader is obliged to summarize the crisis with a question: How is Christian theology to thrive or even survive in the face of the vast sociopolitical changes, migration, and globalization of the last 20-30 years? These changes have completely altered life for nearly all populations around the world and caused an upheaval in everything we do, including the way we understand and practice our faith.

The answer, according to Bevans, is to reimagine theology in a global attitude. Only if we can refashion the concept of theology altogether can we hope to continue practicing it in a world wholly refashioned.

He begins by redefining the word, itself. The term ‘theology’ comes from the Greek ‘Theos’ (‘God’), and ‘logos’ (‘thought’ or ‘word’) = ‘thinking or speaking of God’. As Augustine concludes rather sensibly, “Theology is the science of God.”

But Bevans points out a fatal error in this logic: God can never be fully known, and can therefore never be an object of our study since we could never be sure whether it was God we were studying or something else. Bevans offers a litany of Scriptural and Traditional arguments to underscore the point, from Exodus to Isaiah, from the Gospel of John to 1 Timothy, and from Augustine to Aquinas. They all say the same thing, summarized by Aquinas’ quote from the Summa: “Because we cannot know what God is, but rather what He is not, we have no means of considering how God is, but rather how He is not.” It doesn’t make sense to have a science of God because we could never fully know what it is that we’re studying.

Bevans makes it clear that this does not mean that we cannot know God at all, but rather that we cannot know God in the typical way that come to know earthly things like threads and thyroids. Unlike threads and thyroids, Theos is a mystery. We come to know the mystery that is Theos through revelation, and revelation is a personal encounter. Thus, theology can only be subjective, or contingent on the perspective of the individual ‘doing’ the theology. Bevans states it plainly: “There is no purely ‘objective’ theology.” It can only be personal, subjective, contextual.

JOAN: “I hear voices telling me what to do. They come from God.”

George Bernard Shaw, St. Joan.

ROBERT: “They come from your imagination.”

JOAN: “Of course. That is how the messages of God come to us.”

The definition he arrives at for ‘theology’ is the useful if simple phrase, ‘faith seeking understanding’. While it seems sanitary enough, this subtle change in terminology represents a shift to subjective theology and a revolution in the Christian tradition. Subjective theology can be a powerful tool to bridge differing cultures, but without a complementary objective theology can lead to relativism, and, ultimately risks disintegrating the very community it aims to create.

To begin, it must be admitted that a subjective approach to theology is well founded given the argument laid out by Bevans. No one can deny that humans view the world from different perspectives. As individuals with our own bodies, minds, and souls, we experience the world in ways different from everyone else. Differing worldviews lead to differing actions. As such, all humans will approach a given thing in different ways. This applies to Theology as much as it applies to a thread or a thyroid. As Bevans puts it, one’s worldview affects what theological sources one pays attention to. How one interprets Revelation affects how one practices doctrine. And so, inasmuch as Theology is a discipline practiced by human beings, like all disciplines practiced by human beings, it must be subjective or contextual.

We see this in the history of Christian theology and the many forms that the faith has become manifest as: In the first millennium alone Christianity was embodied by three vastly different cultures—the Hebraic, Hellenic, and Byzantine. Through the ages, punctuated by the several councils and synods, the Church has evolved to speak to radically differing people. The fact that the Church changes at all, and especially that it changes as much as it has through the various councils and synods, is proof that it is at least somewhat based in a subjective theology. It must appeal to and make sense to different groups across time and cultures.

This is one of the great beauties of the Church—that it can appeal to so many varieties of people. One reason we have so many religious orders and congregations is that the faith can be investigated and expressed in such a variety of ways. Some sources list some forty orders and five times as many congregations. Not to mention the array of ministries and apostolates that lay parishioners engage in. If theology weren’t subjective, such a kaleidoscopic faith would be unthinkable.

For Bevans, the real profit of subjective theology is seen in the new global paradigm. The fact is that the circumstances that gave rise to today’s Church, a relatively homogenous and protected culture, is no longer extant, having given rise to a volatile, uncertain, and complex intermingling of cultures. We can no longer rely on the static uniformity that characterized the premodern or even early modern Church. As Phan puts it, “the erstwhile consensus has vanished.”

This has rendered the old, objective approach to theology impotent. In the current milieu, ‘the science of God’ comes across as presumptive and imperialistic, not only ineffective, but divisive and counterproductive. In contrast, subjective theology offers a way for missionaries to connect with others and share the Word using the home culture as a basis. Practitioners of subjective theology begin with the premise that knowing God is a personal experience and that one’s context, and thus one’s interpretation, culture, and tradition, play an integral role in how one comes to know God.

As Bevans states, “Every genuine theology is a contextual theology.” And this is how we’ve come to deprecate Theology per se and rather emphasize Filipino theology and Nigerian theology, black American theology and feminist theology, liberation theology and LBGT, etc., etc., theology. There is no longer a single, universal theology that can supposedly speak to everyone. There are only personal theologies that can speak to individuals.

While there can be no doubt that the subjective approach to theology is promising in the new global paradigm, it presents dangers of its own and threatens to hinder or even disintegrate the very community that it aims to create.

First, we must question the premise that there is no such thing as objective theology. Suspicion arises when we consider the fact that Christianity has lasted so long and been manifest in so many different ways across so many different cultures. Clearly, the fact that the faith has permeated so many peoples means that it is malleable, subjective. But the fact that it is recognized as one faith despite the multiplicity means that it is also constant, objective. There is a continuity in the faith as it morphs from culture to culture, and that continuity indicates an objective basis.

Just as a human being is a single, continuous person throughout the ages of life and the ceaseless cycling through of his body’s cells and organs, so too is the Church a single, continuous entity throughout the transformations of culture. A human being has a soul that defines him no matter what happens to his bodily self. Similarly, there is a set of core, unchanging truths that the Church was founded on and have served as the basis for the faith no matter what cultural shifts occur around it. And this set of core, unchanging truths is what we might call the objective theology. The speculative onlooker might recognize it in the Creed. As long as the Church maintains this, it will remain; and if it is ever abandoned, so too will the Church be abandoned.

The real problem with subjective theology is epistemological. If we use as a premise the notion that God can only be known subjectively, then there can be no way to verify whether that knowledge is true or false. If there is no objective, universal standard against which we might prove or disprove a given theological assertion, then anyone’s experience of God must be accepted as true, no matter how preposterous it is. Now, this is not so much an issue if one experiences Theos as a thread or a thyroid, but it does become problematic when one experiences Theos as a thief or a thrashing.

Subjective theology has naturally led to a multiplication of theologies based on the practitioner’s context. Of course, contexts are countless, and so too would theologies be. In this way Christianity begins to resemble Hinduism with its 330,000,000 gods, one for each practitioner. Perhaps there are more since each practitioner could have multiple contexts upon which to build new theologies. At a conference last year, I stumbled upon a session titled ‘NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism’. The possibilities are endless.

What’s more troubling, however, is the fact that epistemological uncertainty can and often does lead to metaphysical uncertainty. If we believe that we cannot know God fully, it is a short step to the belief that God does not fully exist, or that He exists fully in our own heads. If the only evidence of God is personal and subjective, then there is nothing preventing us from believing that God, Himself, is personal and subjective. But if anything is not personal and subjective it is God. And so the subjective theologian is confronted by the possibility that there is no God.

Subjectivity begets relativism and relativism begets atheism just as nominalism begets positivism and positivism begets nihilism.

This is nothing new. Taking a step back, we see this pattern arise during any time of cultural disruption. Any time peoples meet, whether through cooperation or conflict, they are exposed to new ideas and clashing customs, many of which connect to the people’s fundamental beliefs of life and faith. The result is almost always some degree of a shaking the faith and ultimately a breakdown of dogma. It happened in Roman times as it happened in the Reformation. It is no mystery that in an age of sweeping globalization that atheism is on the rise.

Far from being the unitive force that some might have had it, we find that subjective theology can actually be a detriment to the community many purport it to foster. Simply put, subjective theology stresses the contextual, and, by nature, contexts divide. When there is no emphasis on an objective truth that all can agree upon, the inevitable result is a splintering. We see it today on the broad plane of Western Civilization: Relativism has degraded our shared vision, the absence of which has led to a brand of tribalism that we haven’t seen in centuries.

If we are to confront the global paradigm with a fresh conception of theology, we need to consider the subjective aspect. But we cannot limit our approach to the subjective. Combining the subjective with the objective allows for a robust evangelism and guards against the pitfalls of relativism.

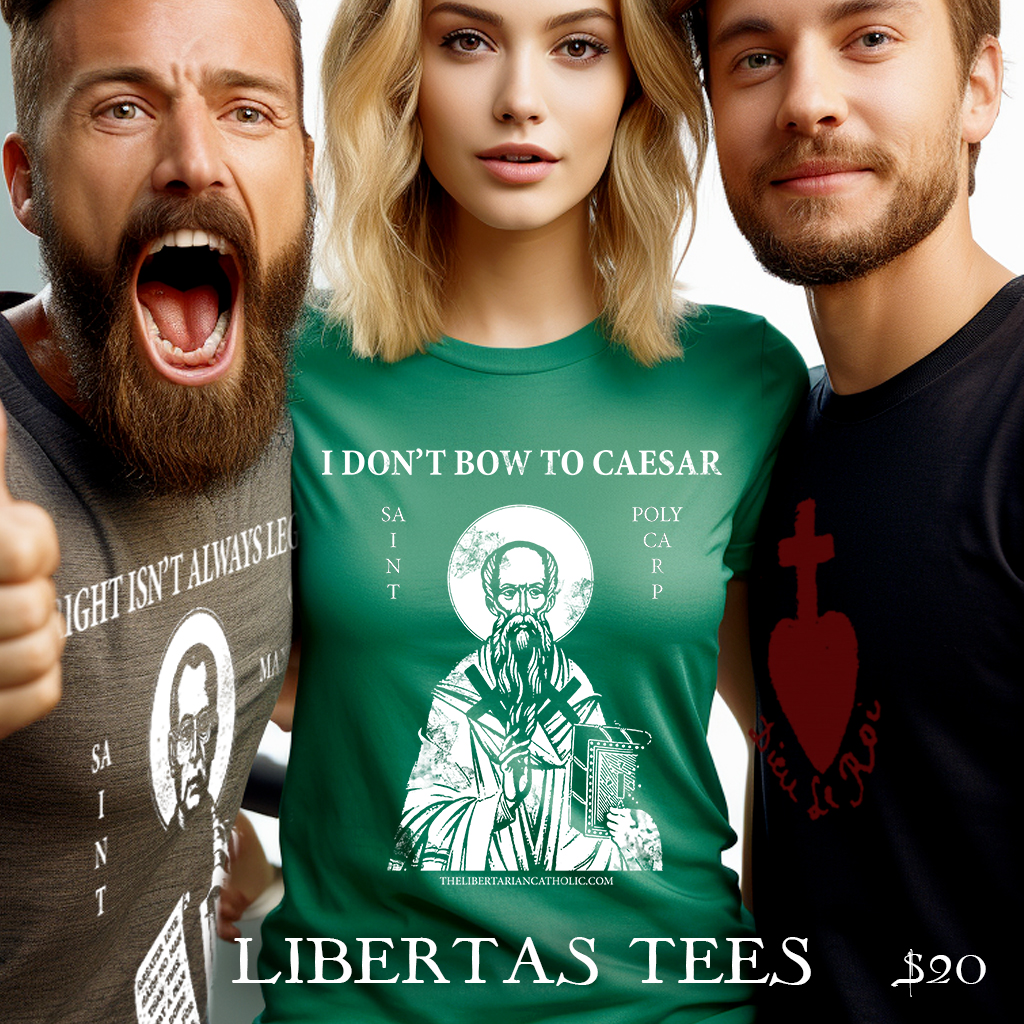

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic