When accordingly it is inquired, whence is evil, it must first be inquired,

what is evil, which is nothing else than corruption,

either of the measure, or the form, or the order, that belong to nature.

– St. Augustine

The study of Western Civilization has been all but eradicated. This was no accident but, rather, an aggressive policy of leftist academe which has used exclusionary tactics to dominate and pervert the culture and purpose of our universities since the 1960s and 70s.[1] But, for us students, driven underground, Western history is the greatest treasure trove of almost every faculty. Not least of these is natural law.

This unique philosophy of law so encapsulated the spirit of the West that the late Prof. Surya P. Sinha described law as ‘the most central principle of [the] social organization’ of Western civilization alone. ‘This fact explains that most…theories about law have issued from the Western culture’.[2] Prof. Sinha even declared law itself to be a non-universal phenomenon of the West, other civilizations developing little more than ‘principles of moral life which are not law’.[3]

The story of natural law is a fascinating one; Prof. Ricardo Duchesne draws from decades of definitive scholarship on the uniqueness of the West to crystallize the ‘essential message’ from across the social sciences: ‘the rise of the West is the story of the realization of humans who think of themselves as self-determining and therefore accept as authoritative only those norms and institutions that can be seen to be congenial with their awareness of themselves as free and rational agents.’[4] Being at the heart of Western civilization, yet lost to history and shrouded in confusion, I would like to clarify the environment in which natural law developed and the consequences of its loss.

In this three-part article, I will discuss:

- The Indo-European, cultural origins of natural law;

- The Roman, statist confusion of natural law; and

- The Church’s rightful title as successor in this tradition.

The Origins of Natural Law

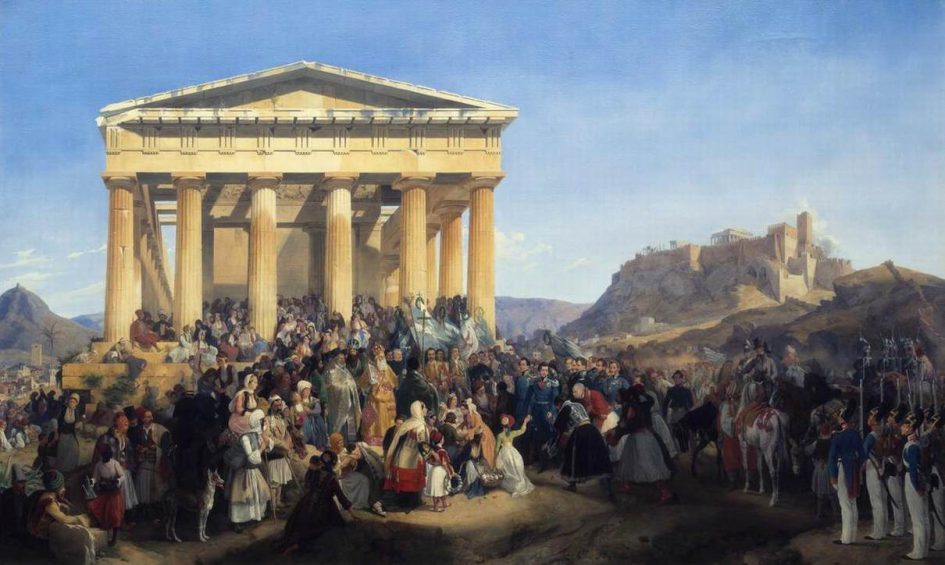

I propose that natural law concepts germinated in the aristocratic culture of the Indo-European environment of ancient Greece and were nurtured by Christianity (a thoroughly Hellenistic religion); thus, why the Church found many similar concepts of kingship in the medieval Indo-European tribes of Northern Europe, particularly the rule of law and the right of resistance against tyrants. This allowed for the transition to and development of natural law and the Church’s creation of the first proper system of law in the world (discussed further in part 3).

The classical natural law school of jurisprudence was concerned with the use of reason to discover the natural order of the world, particularly the world of men. This involved discovering universal rights which, by definition, cannot be alienated from anyone by anyone, rendering all subject to this natural justice. Thus, the natural law rules as king of kings, rather than governing coercively as the legislated whim of a despot. But, natural law was no accidental discovery; Prof. Sinha noted, ‘the inquiring mind of the Greeks…failed to find an agreement among the priestly experts of the Middle East on fundamental questions [and so] they, in Ionia, began thinking about these questions themselves… Instead, they used natural law to explain the phenomena.’[5]

The universe then was considered ordered, perhaps even controllable – not the incomprehensible and whimsical actions of untouchable gods. Natural phenomena had natural causes, according to pre-Socratic Thales of Miletus, and the same philosophy which saw the cosmos as a natural order applied to human societies too. This created environments less hospitable to those who would set themselves up as the sole source of social order; indeed, some of the Greek poleis were governed by the rule of law.[6]

Sinha concludes that the ancient Greek’s desire to live ‘for his own sake…marks the emergence of individualism.’ However, he asserts this individualistic rejection of oriental despots and unquestionable sage wisdom originates merely in the environmental factors of the Greek archipelago, in the shadow of the collapsed Mycenaean Kingdom.[7] Whilst such thinking is typical in today’s academe, Prof. Duchesne’s theory is more thorough:

‘[T]he individualism of the Homeric heroes came originally from the Indo-European chieftains who took over the Greek mainland in the second millennium, and founded Mycenaean culture. [Thus] the primordial roots of Western uniqueness must be traced back to the aristocratic warlike culture of the Indo-European speakers who spread throughout Europe during the 4th and 3rd millennium [B.C.].’[8]

The uniqueness of the Indo-European egalitarian aristocracy was the freedom (and even encouragement) of individuals to strive for personal recognition – a Nietzschean ‘restless ethos’ in which berserkers flaunted their fearlessness in combat to earn respect and nobility.[9] The aristocracy (from the Greek for excellent or virtuous being – ‘aristos’) were thus the nobles of a society whose virtues were martial and masculine, evidenced by the brotherhoods/war-bands of free men. The individualistic nature of these ‘free aristocrats’ was not that of ‘an autocrat who treats the upper classes as unequal servants but as “peers” who exist in a spirit of equality as warriors of noble birth.’[10]

Naturally, the mainspring of Western Civilization’s concern for liberty was the Indo-European culture of self-asserting, audacious individuals who continually competed against those who would create a territorial monopoly of judicial power, keeping not just despotic rule but any state creating activity at bay. It was the inheritance of this ethos which caused the ancient Greeks to see the Oriental practice of prostration before the ‘Great King’ as ‘symbolic confirmation of the great divergence between Eastern and Hellenic notions of individualism and political authority.’[11] Most significantly, however, was the recounting of the individual heroic deeds of the aristos by the priestly class.

In depicting heroic deeds, the Indo-European spirit was internalized by the intellectual class of priests. This produced a highly competitive philosophical environment – ‘the miracle of Greece’ – which drove the aristos to greater feats of rational self-mastery, as Prof. Duchesne expounds:

From Homer on, new standards of arête [virtue] began to evolve away from a strictly martial conception. Odysseus, the central character of the Odyssey, is seen to create meaning in his life not by risking his life in battles, but in his roles of spouse, parent, and joyful companion to his friends…

The ultimate basis of Greek civic and cultural life was the aristocratic ethos of individualism and competitive conflict which pervaded IE culture. Ionian literature was far from the world of berserkers but it was nonetheless just as intensively competitive. New works of drama, philosophy, and music were expounded in the first-person form as an adversarial or athletic contest in the pursuit of truth… The search for the truth was a free-for-all with each philosopher competing for intellectual prestige in a polemical tone that sought to discredit the theories of others while promoting one’s own.[12]

So, the western concept of virtue (from virtus, the Roman, aristocratic concept of manliness) evolved from attributes associated with martial valour to those of the rational and civil man. In contrast to the violent hubris of Achilles, a new virtue emerged – ‘Sophrosyne, referring to moderation or self-restraint’.

‘This virtue of moderation, it is argued, was suitable to the life of democratic discussion in the polis, which required self-control and “sound mind.” This new virtue challenged the elitist view of the heroic age as a time when the social order was under the spell of mighty and turbulent aristocrats thirsting for glory and plunder without consideration for the pain and hardship they brought onto the world.’[13]

Basically, the Greeks internalized the restless, conquering Indo-European spirit; philosophy and poetry began to depict their inner battles as well as outer. High competition in understanding the complexity of human reason, the psyche and society had begun. Rather than simply overpowering the world around them, even the gods, man turned inward to conquer himself, producing the self-civilizing, trustworthy proto-gentleman who pursued Plato’s four cardinal virtues – prudence, justice, temperance and courage.

In part 2, I will discuss the ancient Roman’s statist confusion of natural law.

(Originally published at The Ludwig von Mises Centre website – MisesUK.org)

[1] See Duchesne, R. (2011) The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, Leiden: Brill

[2] Sinha, S. P. (1993) Jurisprudence Legal Philosophy: In a Nutshell, St. Paul, Minn.: West Pub. Co., p.8

[3] Sinha, S. P. (1995) ‘Non-Universality of Law’, ARSP: Archiv Für Rechts- Und Sozialphilosophie / Archives for Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy, 81(2), pp.185–214

[4] Duchesne, R. (2011). The Uniqueness of Western Civilization. Leiden: Brill. p. 270

[5] Ibid., p.10

[6] Ober, J. (2015) The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece, Princeton University Press, Preface xv

[7] Sinha, S. P. (1993) Jurisprudence Legal Philosophy: In a Nutshell, St. Paul, Minn.: West Pub. Co., p.8

[8] Duchesne, R. (2011) The Uniqueness of Western Civilization. Leiden: Brill, p. 344

[9] Ibid., p. 368

[10] Ibid., pp. 372-373

[11] Ibid., p. 380

[12] Duchesne, R. (2011) The Uniqueness of Western Civilization. Leiden: Brill, pp.450 & 452

[13] Ibid., p.342

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic