If there is one thing that makes us Catholic, it is the Eucharist. As it is said in the Catechism, “the Eucharist is ‘the source and summit of the Christian life.’”

That is why it was so alarming to hear the 2019 Pew Research Center findings that only 31 percent of self-described Catholics believe that, “during Catholic Mass, the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Jesus”. If one does not believe in the real presence, can one truly be considered a faithful Catholic?

In response to the findings, the USCCB launched a three-year initiative called the Eucharistic Revival. Its mission: “To renew the Church by enkindling a living relationship with the Lord Jesus Christ in the Holy Eucharist.” The first year of the revival started in 2022 and was focused on diocesan renewal, the second year started in 2023 and is dedicated to parish-level events and listening sessions, and the third year will begin with a pilgrimage from each side of the country and ending in Indianapolis for the National Eucharistic Congress July 17-24.

Great Expectations

When I first heard about it, I was thrilled. I thought, finally, we have a chance to participate in the Church’s governance and direction and possibly help bring about a restoration of its glory. But, as I joined in the events, I quickly realized the entire approach was limited and possibly misguided. Events centered on adoration education, naturally, but also featured folksy praise and worship music, group prayer ‘Encounter Nights’, and listening sessions that focused on parish community life.

Despite the fanfare, one thing was noticeably neglected from the initiative as a whole—the Mass. This is problematic for a revival of the Eucharist because the Mass is the dwelling place of the Liturgy of the Eucharist and center of our faith. Without proper attention to the Mass, all the praise music and encounters won’t do a thing.

Lex orandi, lex credendi. The way we pray is the way we believe. We must look to the order of the Mass to better understand our relationship to the Eucharist.

I am reminded of the city planners who hope to reduce speeding down a residential street by placing speed limit signs along the side. The drivers might notice the signs and they might even want to slow down, but as long as the streets are wide and there are no obstructions anywhere in sight, they will continue to speed and cause accidents.

In a similar way, the infrastructure around the Eucharist will affect how people interact with it, no matter what signs or education we direct toward it. The problem is that the infrastructure around the Eucharist is not built for reverence or adoration. On the contrary, it is built for unbelief.

The Elephant in the Room

Though the motive behind the Eucharistic Revival is admirable, it is clear that all of the discussion around it is neglecting the seven-ton wooly mammoth in the room. Over the course of the last hundred years, the Church has undergone a transformation that has rearranged prayers, upended tradition, and made it nearly impossible for the faithful to regularly celebrate a holy and reverent Liturgy. How can we seriously ask why lay Catholics don’t believe in the real presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist when it is not even clear that church authorities believe any more?

The transformation has transpired along two lines: First, the modernization and Protestantization of church architecture, and second, the liturgical reforms around the Second Vatican Council.

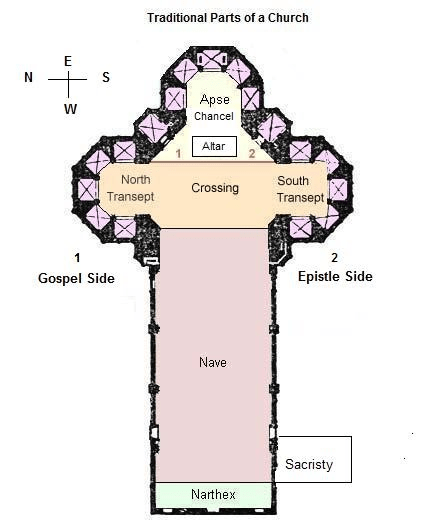

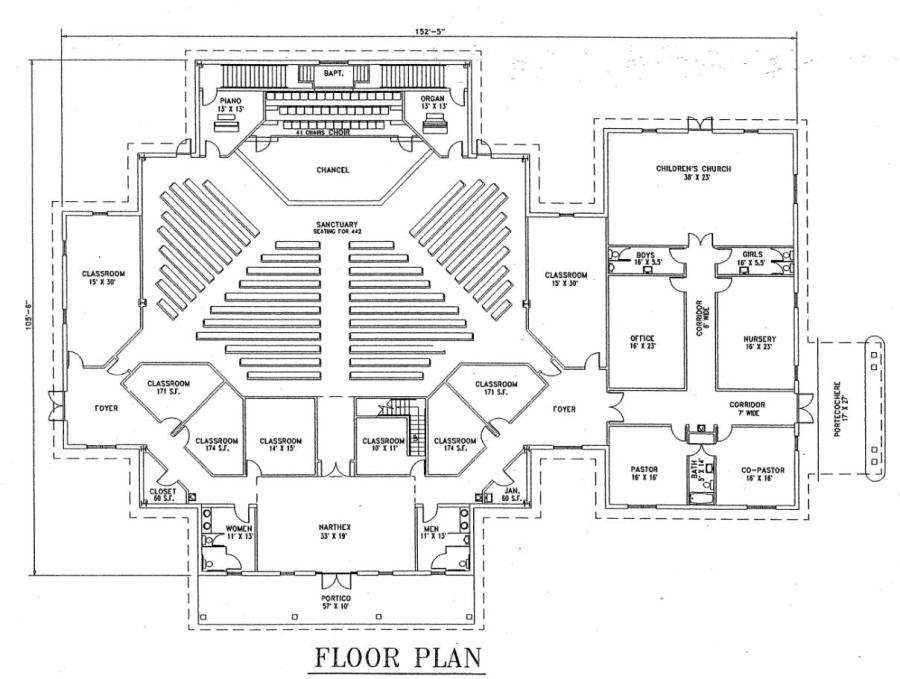

First, there can be no doubt that the architecture of a church can profoundly influence the liturgical experience and the congregation’s focus. Up until around 1930, Catholic churches had been built with the Mass and the Eucharist in mind. Churches were for the most part cruciform, with the congregation facing the altar, placed in the center of the apse chancel. Notwithstanding local architectural vernaculars, churches were vertical in orientation, enabling a focus on the altar and opening up a path upward toward Heaven.

Around the turn of the 20th century, progressive clergy in Europe, notably Dominican Father Pierre Marie-Alan Couturier, began incorporating Protestant ‘church in the round’ styles as well as modern minimalism as a way to keep up with the times. While church architecture in the United States remained traditional up to the 1930s, the Great Depression slowed construction and convinced a critical mass of clergy to do away with the heavy, expensive builds of the previous age. From the 1940s on, modernism reigned.

There are a number of problems with modernist church architecture, but the most relevant is that it obliterates the potential for reverence of the Eucharist. Modernist church architecture often features a horizontal layout with the ‘church in the round’, with no particular focus except perhaps the coughing Boomers across the aisle. Visitors will not be able to identify the tabernacle, most likely because it’s not behind the altar, but somewhere else out of sight. Nor will they be particularly inspired by the cold Yugoslavian-era cinder block walls behind an abstract crucifix. Most modernist churches are devoid of any sacred art, opting instead for dismal, Gulag-inspired stations that they might put on display.

Irreverence Ingrained

Second, the liturgical reforms initiated by the Second Vatican Council introduced significant changes, such as the use of vernacular languages and the Novus Ordo Mass, which allowed priests to face the congregation (versus populum) during the Mass and removed substantial sections of the liturgy. As a part of the reforms, in the 1960s and ‘70s, clergy removed communion rails and began serving both the Body and Blood of Christ during communion. In 1983, Cannon Law was updated to allow for extraordinary ministers, or lay members of the congregation, and to distribute communion into the hand of the standing faithful.

While these changes aimed to make the liturgy more accessible, they also tended to eliminate the inherent reverence of a priest facing the altar during the Eucharistic prayer and the faithful receiving the Precious Body on the tongue while kneeling in traditional Roman rite. Far from the rigidly controlled distribution of the Body and Blood, at the Novus Ordo Mass you might find an old lady with a sports jersey and spandex pants handing out hosts like Halloween candy. I have even seen a priest call up the congregation to the apse chancel behind the altar to hold hands while taking communion.

Soon after the Novus Ordo Mass was instituted in 1970, traditionalists sensed issues with the new rite, but found it to be inexorable. French archbishop Marcel Lefebvre formed a seminary and eventually the Society of St. Pius X to preserve the traditional Mass but faced constant pushback. Through negotiations with Pope Paul VI and John Paul II, Lefebvre secured and indult that permitted priests to perform the traditional Mass in a limited capacity. Later, Benedict XVI’s 2007 Summorum Pontificum further expanded priests’ rights to celebrate traditional Mass, though Pope Francis abrogated Benedict XVI’s letter with his 2021 Traditiones custodes, again restricting the celebration of the traditional Mass.

Toward True Revival

At my parish listening session, the question was asked how it is possible that so few Catholics believe in the real presence. Everyone seemed mystified because the parish community is so strong with over 100 ministries and standing room only Sunday Masses. And yet the church is the quintessential church in the round, the tabernacle is not housed behind the altar, there is no beautiful sacred art, and communion is distributed in a haphazard manner all around the nave. Considering the concerted effort to ‘get beyond’ traditional church architecture and the radical upheaval of the liturgy instituted since Vatican II, the answer is clear.

There is no doubt that there is a need for Eucharistic revival and the USCCB’s initiative is commendable. But, if they are to achieve true Eucharistic revival, they must address the underlying issues that have led to the current disbelief. The modernization of the Church, both in its architecture and liturgy, and the marginalization of the traditional Latin Mass have created an environment where reverence and a living relationship with Christ in the Eucharist are increasingly difficult to maintain. A genuine revival will require not only a re-education of the faithful but also a re-evaluation of the spaces and forms of worship that shape their faith experience.

These are doubtless gigantic undertakings and we cannot hope to accomplish them in three years like the Eucharistic Revival set out to do. But all such efforts must have a start and the best place to start is in an honest conversation. Perhaps the Eucharistic Congress is the place for that conversation.

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic