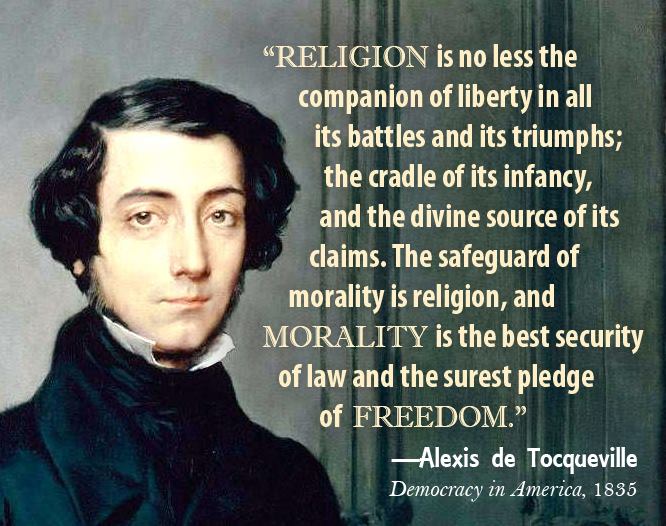

Writer and statesman, born at Verneuil, Department of Seine-et-Oise, 29 July 1805; died at Cannes, 16 April, 1859. He was the great grandson of Malesherbes, the defender of Louis XVI. As a judge at Versailles in 1830 he formed a friendship with Gustave de Beaumont, with whom he traveled to America in 1831. Tocqueville’s letters show that he foresaw what strides the Church was destined to make in America and likewise the dogmatic nothingness which would result from Unitarianism and the absurdities of Illuminism. Two publications resulted from this journey; the collective work of two friends published under the title “Du système pénitentiaire aux Etats-Unis et de son Application en France”; the second, Tocqueville’s personal work, is the celebrated book “Democracy in America“, of which the first volume appeared in 1835 and the second in 1840. The work won for Tocqueville admission to the Académie des sciences morales et politiques (1838) and French Academy (1841).

In Democracy in America, de Tocqueville stressed the dependence of freedom on religion, “For my own part, I doubt whether man can ever support at the same time complete religious independence and entire public freedom. And I am inclined to think, that if faith be wanting in him, he must serve; and if he be free, he must believe.”

Historian Alan Kahan writes:

While Tocqueville was a strong supporter of the separation of Church and State, he was also a strong supporter of the practice of religion. Indeed, although he did not comment on it directly, he would have been a strong supporter of the “free exercise” clause of the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” (emphasis added).

Rather than attempting to push religion out of the public sphere, he welcomed it, provided that its influence was indirect and it did not try to turn the public sphere in its own domain. Unlike current French law, he would have had no hesitation about letting students, or teachers, wear headscarves or crosses or yarmulkes in a public classroom (a student or teacher leading in a prayer in a classroom would be another matter, however). In his own day Tocqueville rejected the militant secularism that saw religion as the enemy, and there is no reason to believe he would have changed his mind today. He rejected equally the claim of some religious people that freedom was the enemy of religion. For Tocqueville, the only way for either freedom or religion to prosper in the long run was by recognizing that they were mutually necessary, and mutually beneficial.

On religion and freedom, Tocqueville wrote:

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic