In both my writing, my research and my personal life, I’ve always been attracted, or maybe guided towards the link between madness, geniality and poetry.

Not because of some stereotype about some eccentrics being geniuses, or the recurrence of certain people with emotional and mental struggles being savants in certain areas or with certain skills.

It’s more because of a rather personal pattern I’ve realized in my own writing and my ever-changing mood, with some of my most well developed pieces getting done and finished under the distress of a myriad of emotions while some of my most (in my own opinion) mediocre and simplistic ones getting written as part of a task, usually academic or otherwise.

Some people will still compliment my writing and my use of language to express certain complex ideas, but I’ve always felt my best, most pure, passionate and probably also most unhinged writing is more private in nature.

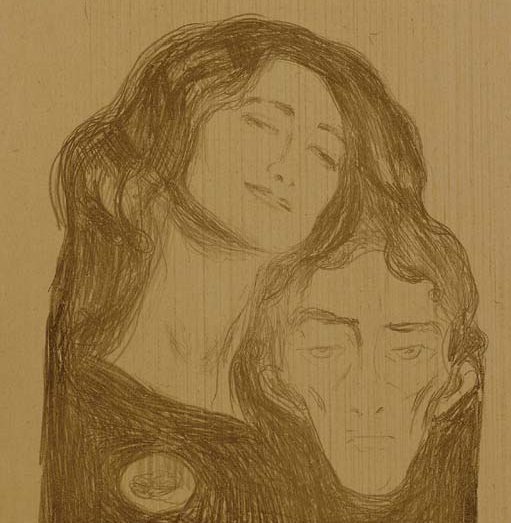

For those who may have had the chance (or misfortune) of reading my poetry, you’ll find in there my attempts at trying to capture the truth and the beauty of my emotions spiraling into something that can be both orderly and chaotic.

I choose poetry rather than prose to express some of my emotions (aside from the occasional epistolary format adopted to deal with large volumes of messages and emotions exchanged with whoever finds herself to have become my unwilling muse) because the relative shortness of a poem, as well as the rhythmic and melodic limitations of it guide me to express my feelings in a constrained way that the extension and relative lack of emotional censorship prose would allow for. In short, poetry orders what prose would unravel in moments of emotional instability.

I write this as of now, having taken some time to digest some words a person very dear to my heart told me recently: “You love like you live: through pain.” This phrase has been circling in my head since the moment I read it, and as I carry on with the weight and consequences of some disorderly emotions, I try to make sense of my own poetry through the lens of my three favorite poets, comparing my craft with the ones of Ezra Pound, Yukio Mishima, and Sting.

The first two would be either an odd choice or a dog whistle about radical right-wing politics. For me, they are neither. I don’t care about Pound the fascist or Mishima the monarchist nationalist about the same as I don’t care about Che Guevara the guerrilla communist. It’s their lives, their emotional struggles and their reflection in their works that I’m invested in.

By the way, Che also wrote poetry, but as a native Spanish speaker myself, I find his poetry rather dull and uninteresting, too partisan to be counted among his best works.

But with Ezra Pound and with Yukio Mishima I feel reflected in other ways, like the complexity of the ideas beneath what appears to be random meanderings, or the apparent simplicity of a few scarce poems here and there closing major works.

With Sting comes a different bound, one based in the growth of a child becoming a man who has been listening to him since a toddler.

My struggle with my emotions is not dissimilar with my struggle with my close reading of the Pisan Cantos, for instance, with erratic attempts at making sense of the words and of their author through countless references to ancient epics and then contemporary prejudices.

Or in the tragic beauty of the death poems of the leader of the Tatenokai as he tried and failed to bring forth his uprising or as it similarly concluded his autobiographical essay about himself and his struggle for bodily perfection.

It is not coincidence both Pound and Mishima have influenced my private poetry, for both also suffered with fluctuating emotions during their lives. For Pound and Mishima, their madness and genius meant narcissism, bipolarity and ultimately depression leading them to their deaths.

I, for one, don’t intend to follow that path, even if it feels rather natural to just follow on their steps as I attempt to grow in their giant shadows.

Instead, I look up to Sting, Gordon Matthew Sumner, the Newcastle bassist who took his name from a stripped rugby shirt he used to wear during his first musical gigs.

Unlike Pound or Mishima, Sting was no professional in the area of literature, at least not like them. An English teacher and even a construction worker in the shipyards of his hometown, Sting took up his talent with words to write music, which with his band, The Police, became globally popular, and as a solo artist, became a vehicle for more personal messages about his self and his life.

At one time called the worst lyricist ever, Sting’s songs are filled with forced rhymes and literally references, a callback to his career as a teacher, but also to more mundane things, like his childhood environment among ships, his country as an English national, or his complex relationships with his parents and his first and second wife.

And like Mishima and Pound, Sting has also suffered with emotional burdens through his life and career, his songwriting reflecting sadness, melancholy, depression, passion, mania, obsession, even up to the level of dreamscapes.

His work is also a conveyed show of the constant war some of us fight in our heads, and some of his solo albums make no effort in covering those resentments, feelings of abandonment, conflicting push-and-pulls, and even treatments to deal with them.

Mentioning the specific albums and songs by Sting, and each reference there is to his struggle with his emotional disorder, in that sense, could take me as much as trying to retake my reading of the Pisan Cantos only for their larger contemporary cultural value.

But what changes with Sting compared to Pound or Mishima is that what prevails in his work is love, not pessimism, not duty. Sting is a bard of love and belief, even in the dryest dessert or the poorest shipping town.

And this is why I try to follow Sting as my go-to-poet more than Ezra Pound or Yukio Mishima, for the complexity of the first or the outright beauty of the second cannot compel the full range and spectrum of my emotions in their internal conflict as much as a poetry meant to be be sung aloud with music.

My poetry may still be private, meant for the eyes of my friends in their sadness, and specially for my muses in my shortsighted infatuations, but they intend to become a testament to my life and my emotions.

For all my failed loves reject to become empty vessels of my disorderly beauty, fearing my pain might break them, I still hope about finding the one that will trascend my desire.

But for now she might simply stay as my dear, my darling, my beautiful Desirée…

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic