Five cardinals sent a set of questions known as dubia to Pope Francis to express their concerns and seek clarification on points of doctrine and discipline ahead of the opening of the Synod on Synodality at the Vatican.

Dubia are questions brought before the pope and the appropriate Vatican office that seek a simple “Yes” or “No” response in order to clarify disputed matters of Catholic teaching and practice.

The prelates — German Cardinal Walter Brandmüller, American Cardinal Raymond Burke, Chinese Cardinal Zen Ze-Kiun, Mexican Cardinal Juan Sandoval Íñiguez and Guinean Cardinal Robert Sarah — had submitted an earlier version of their dubia on July 10 and received a reply the following day.

Because the Pope answered at length — and not with the customary “Yes” or “No” — the group resubmitted their dubia in August in order to get clarification. The Pope has not responded to the August set of dubia.

1. Dubium about the claim that we should reinterpret divine Revelation according to the cultural and anthropological changes in vogue

After the statements of some bishops, which have been neither corrected nor retracted, it is asked whether in the Church divine Revelation should be reinterpreted according to the cultural changes of our time and according to the new anthropological vision that these changes promote; or whether divine Revelation is binding forever, immutable and therefore not to be contradicted, according to the dictum of the Second Vatican Council, that to God who reveals is due “the obedience of faith” (Dei Verbum, 5); that what is revealed for the salvation of all must remain “in their entirety, throughout the ages” and alive, and be “transmitted to all generations” (7); and that the progress of understanding does not imply any change in the truth of things and words, because faith has been “handed on … once and for all” (8), and the magisterium is not superior to the word of God, but teaches only what has been handed on (10).

Pope Francis’ response: a) The answer depends on the meaning you give to the word “reinterpret.” If it is understood as “to interpret better,” the expression is valid. In this sense the Second Vatican Council affirmed that it is necessary that with the work of the exegetes — I would add of the theologians — “the judgment of the Church may mature” (Cone. Ecum. Vat. II, Const. Dogm. Dei Verbum, 12).

b) Therefore, while it is true that divine Revelation is immutable and always binding, the Church must be humble and recognize that she never exhausts its unfathomable richness and needs to grow in her understanding.

c) Therefore, she also matures in the understanding of what she herself has affirmed in her magisterium.

d) Cultural changes and the new challenges of history do not modify the revelation, but they can stimulate us to make more explicit some aspects of its overflowing richness, which always offers more.

e) It is inevitable that this may lead to a better expression of some past statements of the magisterium, and indeed it has happened throughout history.

f) On the other hand, it is true that the magisterium is not superior to the word of God, but it is also true that both the texts of Scripture and the testimonies of tradition need an interpretation that allows us to distinguish their perennial substance from cultural conditioning. It is evident, for example, in biblical texts (such as Exodus 21:20-21) and in some magisterial interventions that tolerated slavery (cf. Nicholas V, Bull Dum Diversas, 1452). This is not a minor issue given its intimate connection with the perennial truth of the inalienable dignity of the human person. These texts are in need of interpretation. The same is true for some New Testament considerations on women (1 Corinthians 11:3-10; 1 Timothy 2:11-14) and for other texts of Scripture and testimonies of tradition that cannot be repeated literally today.

g) It is important to emphasize that what cannot change is what has been revealed “for the salvation of all” (Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, dogmatic constitution Dei Verbum, 7). For this reason, the Church must constantly discern between what is essential for salvation and what is secondary or less directly connected with this goal. In this regard, I would like to recall what St. Thomas Aquinas affirmed: “the more we descend to matters of detail, the more frequently we encounter defects” (Summa Theologiae 1-11, q. 94, art. 4).

h) Finally, a single formulation of a truth can never be adequately understood if it is presented in isolation, isolated from the rich and harmonious context of the whole of revelation. The “hierarchy of truths” also implies situating each of them in adequate connection with the more central truths and with the totality of the Church’s teaching. This can ultimately give rise to different ways of expounding the same doctrine, although “for those who long for a monolithic body of doctrine guarded by all and leaving no room for nuance, this might appear as undesirable and leading to confusion. But in fact such variety serves to bring out and develop different facets of the inexhaustible riches of the Gospel” (Evangelii Gaudium, 49). Each theological line has its risks but also its opportunities.

2. Dubium about the claim that the widespread practice of the blessing of same-sex unions would be in accord with revelation and the magisterium (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2357)

According to divine Revelation, confirmed in sacred Scripture, which the Church “with a divine commission and with the help of the Holy Spirit, … listening to it devoutly, guarding it scrupulously and explaining it faithfully” (Dei Verbum, 10): “In the beginning” God created man in his own image, male and female he created them and blessed them, that they might be fruitful (cf. Genesis 1:27-28), whereby the apostle Paul teaches that to deny sexual difference is the consequence of the denial of the Creator (Romans 1:24-32). It is asked: Can the Church derogate from this “principle,” objectively sinful such as same-sex unions, without betraying revealed doctrine?

Pope Francis’ response: a) The Church has a very clear conception of marriage: an exclusive, stable, and indissoluble union between a man and a woman, naturally open to the begetting of children. It calls this union “marriage.” Other forms of union only realize it “in a partial and analogous way” (Amoris Laetitia, 292), and so they cannot be strictly called “marriage.”

b) It is not a mere question of names, but the reality that we call marriage has a unique essential constitution that demands an exclusive name, not applicable to other realities. It is undoubtedly much more than a mere “ideal.”

c) For this reason the Church avoids any kind of rite or sacramental that could contradict this conviction and give the impression that something that is not marriage is recognized as marriage.

d) In dealing with people, however, we must not lose the pastoral charity that must permeate all our decisions and attitudes. The defense of objective truth is not the only expression of this charity, which is also made up of kindness, patience, understanding, tenderness, and encouragement. Therefore, we cannot become judges who only deny, reject, exclude.

e) For this reason, pastoral prudence must adequately discern whether there are forms of blessing, requested by one or more persons, that do not transmit a mistaken conception of marriage. For when a blessing is requested, one is expressing a request for help from God, a plea for a better life, a trust in a Father who can help us to live better.

f) On the other hand, although there are situations that from an objective point of view are not morally acceptable, pastoral charity itself demands that we do not simply treat as “sinners” other people whose guilt or responsibility may be due to their own fault or responsibility attenuated by various factors that influence subjective imputability (cf. St. John Paul II, Reconciliatio et Paenitentia, 17).

g) Decisions which, in certain circumstances, can form part of pastoral prudence, should not necessarily become a norm. That is to say, it is not appropriate for a diocese, an episcopal conference or any other ecclesial structure to constantly and officially authorize procedures or rites for all kinds of matters, since everything “that is part of a practical discernment in particular circumstances cannot be elevated to the level of a rule,” because this “would lead to an intolerable casuistry” (Amoris Laetitia, 304). Canon law should not and cannot cover everything, nor should the episcopal conferences claim to do so with their various documents and protocols, because the life of the Church runs through many channels in addition to the normative ones.

3. Dubium about the assertion that synodality is a “constitutive element of the Church” (apostolic constitution Episcopalis Communio, 6), so that the Church would, by its very nature, be synodal.

Given that the Synod of Bishops does not represent the College of Bishops but is merely a consultative organ of the pope, since the bishops, as witnesses of the faith, cannot delegate their confession of the truth, it is asked whether synodality can be the supreme regulative criterion of the permanent government of the Church without distorting her constitutive order willed by her Founder, whereby the supreme and full authority of the Church is exercised both by the pope by virtue of his office and by the College of Bishops together with its head, the Roman pontiff (Lumen Gentium, 22).

Pope Francis’ response: a) Although you recognize that the supreme and full authority of the Church is exercised either by the pope because of his office or by the College of Bishops together with its head, the Roman pontiff (cf. Cone. Ecum. Vat. II, Const. dogm. Lumen Gentium, 22), nevertheless with these dubia you yourselves manifest your need to participate, to give your opinion freely and to collaborate, and you are claiming some form of “synodality” in the exercise of my ministry.

b) The Church is a “mystery of missionary communion,” but this communion is not only affective or eternal, but necessarily implies real participation: that not only the hierarchy but all the people of God in different ways and at different levels can make their voice heard and feel part of the Church’s journey. In this sense we can say that synodality, as a style and dynamism, is an essential dimension of the life of the Church. On this point St. John Paul II has said very beautiful things in Novo Millennio Ineunte.

c) It is quite another thing to sacralize or impose a particular synodal methodology that pleases one group, to make it the norm and obligatory channel for all, because this would only lead to “freezing” the synodal journey, ignoring the diverse characteristics of the different particular Churches and the varied richness of the universal Church.

4. Dubium about pastors’ and theologians’ support for the theory that “the theology of the Church has changed” and therefore that priestly ordination can be conferred on women

After the statements of some prelates, which have been neither corrected nor retracted, according to which, with Vatican II, the theology of the Church and the meaning of the Mass has changed, it is asked whether the dictum of the Second Vatican Council is still valid, that “[the common priesthood of the faithful and the ministerial or hierarchical priesthood] differ from one another in essence and not only in degree” (Lumen Gentium, 10) and that presbyters, by virtue of the “sacred power of orders, to offer sacrifice and forgive sins” (Presbyterorum Ordinis, 2), act in the name and in the person of Christ the Mediator, through whom the spiritual sacrifice of the faithful is made perfect. It is furthermore asked whether the teaching of St. John Paul II’s apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, which teaches as a truth to be definitively held the impossibility of conferring priestly ordination on women, is still valid, so that this teaching is no longer subject to change nor to the free discussion of pastors or theologians.

Pope Francis’ response: a) “The common priesthood of the faithful and the ministerial priesthood differ essentially” (Cone. Ecum. Vat. 11, Const. Dogm. Lumen Gentium, 10). It is not convenient to maintain a difference of degree that implies considering the common priesthood of the faithful as something of “second category” or of lesser value (“a lower degree”). Both forms of priesthood mutually enlighten and sustain each other.

b) When St. John Paul II taught that it is necessary to affirm “definitively” the impossibility of conferring priestly ordination on women, he was in no way belittling women and granting supreme power to men. St. John Paul II also affirmed other things. For example, that when we speak of priestly power “we are in the area of function, not of dignity or holiness” (St. John Paul II, Christifideles Laici, 51).

These are words that we have not sufficiently accepted. He also clearly maintained that while the priest alone presides at the Eucharist, the tasks “do not give rise to superiority of one over the other” (St. John Paul II, Christifideles Laici, note 190; cf. Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, declaration Inter Insigniores, VI). I likewise affirm that if the priestly function is “hierarchical,” it should not be understood as a form of domination, but “this structure is totally ordered to the holiness of Christ’s members” (St. John Paul II, Mulieris Dignitatem, 27). If this is not understood and the practical consequences of these distinctions are not drawn, it will be difficult to accept that the priesthood is reserved only to men and we will not be able to recognize the rights of women or the need for them to participate, in various ways, in the leadership of the Church.

c) On the other hand, to be rigorous, let us recognize that a clear and authoritative doctrine has not yet been exhaustively developed about the exact nature of a “definitive statement.” It is not a dogmatic definition, and yet it must be observed by all. No one can publicly contradict it and yet it can be the object of study, as is the case with the validity of ordinations in the Anglican Communion.

5. Dubium about the statement “forgiveness is a human right” and the Holy Father’s insistence on the duty to absolve everyone and always, so that repentance would not be a necessary condition for sacramental absolution.

It is asked whether the teaching of the Council of Trent, according to which the contrition of the penitent, which consists in detesting the sin committed with the intention of sinning no more (Session XIV, Chapter IV: DH 1676), is necessary for the validity of sacramental confession, is still in force, so that the priest must postpone absolution when it is clear that this condition is not fulfilled.

Pope Francis’ response: a) Repentance is necessary for the validity of sacramental absolution and implies the intention not to sin. But there is no mathematics here, and once again I must remind you that the confessional is not a customs house. We are not owners but humble stewards of the sacraments that nourish the faithful, because these gifts of the Lord, more than relics to be guarded, are aids of the Holy Spirit for the life of the people.

b) There are many ways to express regret. Often, in people who have a very wounded self-esteem, pleading guilty is a cruel torture, but the very act of approaching confession is a symbolic expression of repentance and seeking divine help.

c) I would also like to recall that “at times we find it hard to make room for God’s unconditional love in our pastoral activity” (Amoris Laetitia,311), but we must learn to do so. Following St. John Paul II, I maintain that we should not demand from the faithful overly precise and certain proposals for amendment, which in the end end up being abstract or even egotistic, but that even the predictability of a new fall “does not compromise the authenticity of the intention” (St. John Paul II, letter to Cardinal William W. Baum and the participants in the meeting of the cardinal’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. William W. Baum and the participants of the annual course of the Apostolic Penitentiary, 22 March 1996, 5).

d) Finally, it should be clear that all the conditions that are usually placed on the confession are generally not applicable when the person is in a situation of agony, or with very limited mental and psychological capacities.

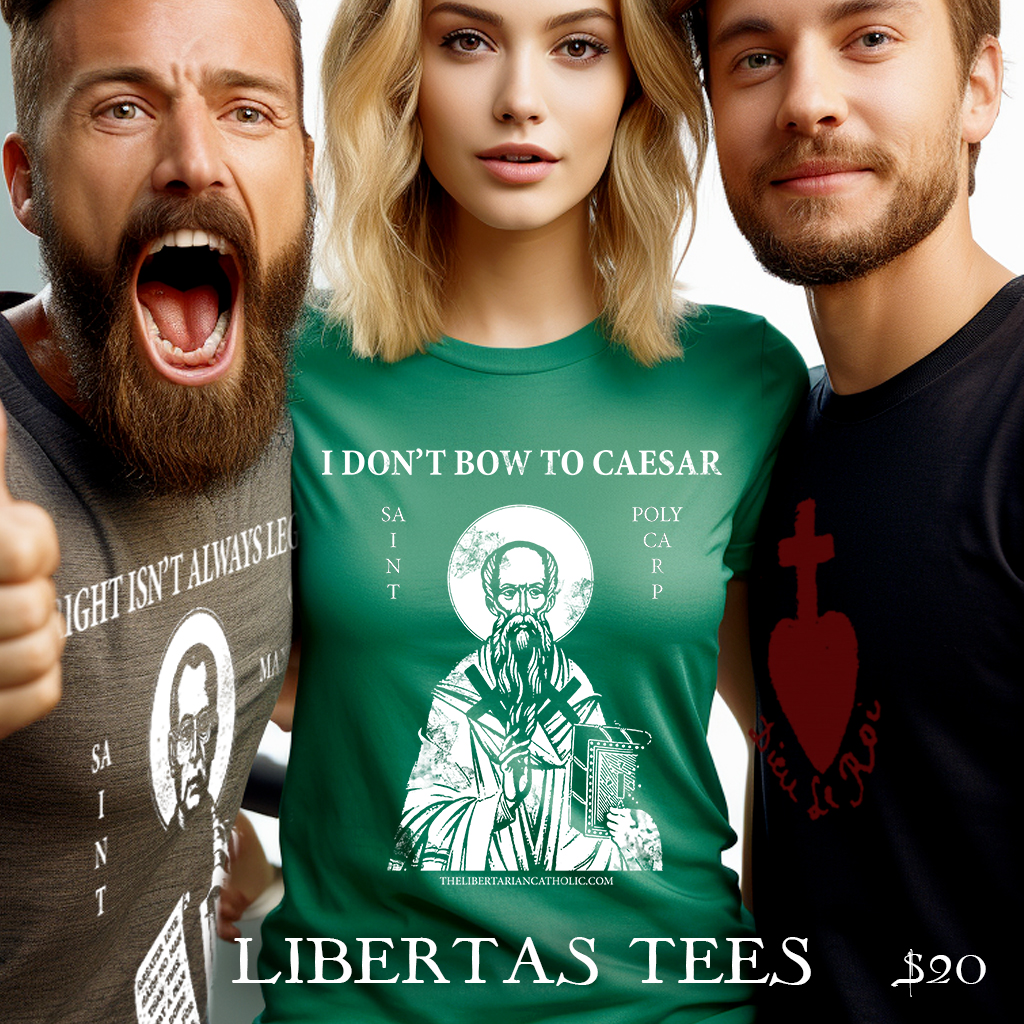

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic