The Holy Roman Empire is often seen as a political structure from a bygone era, with little relevance to modern politics. However, for libertarians and Catholics, the Holy Roman Empire offers a unique and intriguing model for a society based on their values.

History shows that the unique political model maximized the Catholic principles of subsidiarity and solidarity, which facilitated what is considered High Christendom (the High Medieval Age).

Subsidiarity in the Holy Roman Empire

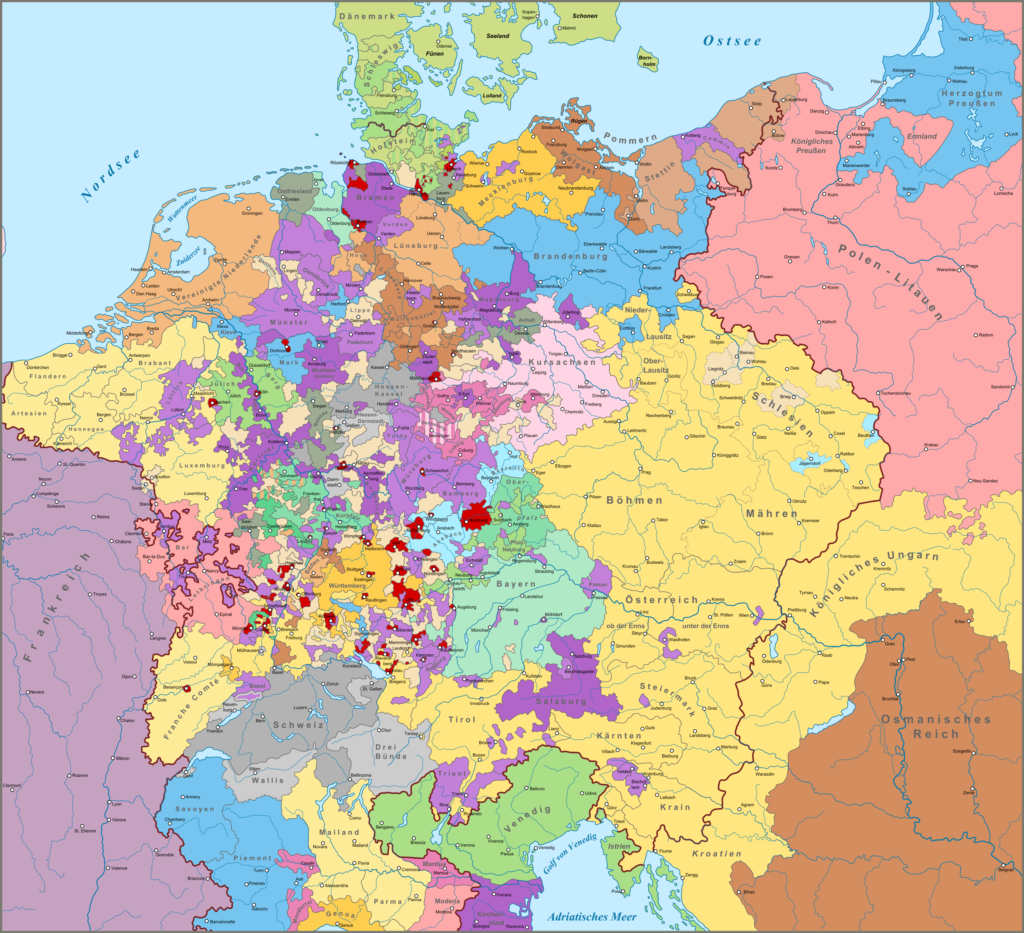

The Holy Roman Empire was a decentralized system of governance, with power divided among the emperor, the imperial Diet (a legislative assembly), the imperial courts, and the various territorial rulers within the empire. This decentralized structure allowed for a great deal of local autonomy, with individual territories and cities having a significant degree of control over their own affairs.

Subsidiarity is the idea that social and economic issues should be dealt with at the most local level possible. This principle holds that decisions affecting individuals and communities should be made as close to them as possible, rather than by a distant central authority. In the Holy Roman Empire, this principle was embodied in the decentralized structure of the empire, which allowed for a significant degree of local autonomy.

For libertarians, this decentralized structure is appealing because it limits the power of the central government and allows for a great deal of individual freedom and autonomy. In the Holy Roman Empire, the central government did not have the power to impose its will on the various territories and cities within the empire, and individuals had a significant degree of control over their own lives and were able to make decisions and govern their territories with a significant degree of independence. For example, cities within the Holy Roman Empire often had their own elected councils, and were able to govern themselves with minimal interference from the central authority.

The Holy Roman Emperor was the figurehead of the empire, but had limited actual power. In practice, the emperor’s authority was largely symbolic, and was used to promote the unity of the empire and to serve as a mediator between the various local authorities. The emperor was elected by a group of electors, who were themselves appointed by various territories and cities within the empire.

This decentralized structure of the Holy Roman Empire was designed to allow for local decision-making and to respect the autonomy of the various territories and cities within the empire. By allowing local authorities to make decisions that were best suited to their individual needs and concerns, the empire was able to promote a sense of community and to foster a sense of shared identity among its citizens.

Solidarity in the Holy Roman Empire

In addition to its decentralized structure, the Holy Roman Empire also has a strong association with Catholicism. The empire was established as a political entity in the 10th century, when the German king Otto I was crowned emperor by the Pope. Over the next several centuries, the empire played a significant role in the spread of Christianity and the development of the Catholic Church.

As such, there was a strong sense of solidarity—individuals and communities working together for the common good. In the Holy Roman Empire, this principle was embodied in the idea of the “Reich,” or the commonwealth of the empire. Despite the decentralization of power within the empire, the various territories and cities within it were united under a common banner and worked together for the greater good of the empire as a whole.

For Catholics, the Holy Roman Empire represents a political structure that was based on their values and beliefs. The empire was a center of Christianity and a bulwark against the spread of secularism and paganism. In the Holy Roman Empire, religion played a central role in society, and the Catholic Church was a powerful force for good, providing education, social services, and spiritual guidance to the people.

The Ideal Libertarian Catholic Political Structure

The combination of subsidiarity and solidarity in the Holy Roman Empire created a unique and enduring political structure. By allowing for local autonomy and decision-making, the empire respected the individual and community-level needs of its citizens. At the same time, the idea of the Reich ensured that these local communities were connected and working together for the greater good of the empire as a whole.

This model of political organization is particularly relevant for modern times, as it addresses the needs and concerns of both individual freedom and the common good. In today’s globalized world, many people feel that decisions are being made by distant central authorities that do not reflect their needs and concerns. At the same time, many people feel that the problems facing our world, such as climate change and economic inequality, cannot be solved by individuals acting alone.

The Holy Roman Empire offers a solution to these modern challenges. By balancing the principles of subsidiarity and solidarity, the empire provides a model for a political structure that respects individual and community-level needs while promoting cooperation and collaboration for the common good. In this way, the Holy Roman Empire can serve as an inspiration and a guide for modern societies seeking to build a more just and equitable world.

In conclusion, the Holy Roman Empire represents an ideal libertarian Catholic political structure. Its decentralized structure limits the power of the central government and allows for individual freedom, autonomy, and subsidiarity while its strong solidarity provides a framework for a society based on Catholic values and beliefs. Although the Holy Roman Empire may seem like a relic from a distant past, its legacy lives on in modern Europe, and its impact on the development of the continent continues to be felt to this day. For libertarians and Catholics, the Holy Roman Empire serves as a model for a society based on freedom, autonomy, and Catholic values, and is a testament to the enduring power of these ideals.

The Libertarian Catholic

The Libertarian Catholic